Leaderboard

-

in Articles

- All areas

- Videos

- Video Comments

- Video Reviews

- Quizzes

- Quiz Comments

- Marker

- Marker Comments

- Books

- Bookshelves Comments

- Bookshelves Reviews

- Bookshelves

- Movies

- Movie Comments

- Movie Reviews

- Aircraft

- Aircraft Comments

- Resources

- Resource Comments

- Tutorials

- Tutorial Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Classifieds

- Classified Comments

- Events

- Event Comments

- Blog Entries

- Blog Comments

- Files

- File Comments

- File Reviews

- Images

- Image Comments

- Albums

- Album Comments

- Topics

- Posts

- Status Updates

- Status Replies

-

All time

-

All time

January 7 2011 - April 4 2025

-

Year

April 4 2024 - April 4 2025

-

Month

March 4 2025 - April 4 2025

-

Week

March 28 2025 - April 4 2025

-

Today

April 4 2025

- Custom Date

-

All time

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 07/01/11 in Articles

-

Nestled deep in a corner of an old packing shed in Dareton, New South Wales a special RAAF aircraft restoration project is taking shape. After two years of painstaking work, volunteers at the Dareton Men's Shed have unveiled the result of their efforts; revealing a magnificent, freshly painted 1954 RAAF CA-27 Sabre Fighter Jet. The next step in the restoration of the Sabre is the wings, which require extensive repair.(ABC Mildura-Swan Hill: Jennifer Douglas) Beneath dust-filled rays of sunlight, the restored metallic fuselage has been transformed by a couple of retired panel beaters who had no previous aviation experience. The Sabre, with its iconic nose cone, is the culmination of the expertise of a dedicated team of retired tradies who meet regularly at their local men's shed. Retired panel beaters Neil McDonald (left) and Greg Wood combined their efforts to restore the Sabre.(ABC Mildura-Swan Hill: Jennifer Douglas) Dareton Men's Shed volunteer and replica Spitfire pilot John Waters says the restoration project is a great example of what the many skilled men's shed members can achieve. "The Sabre's new paint job looks better than it would have straight out of the factory," Mr Waters said. The tail fin and horizontal stabiliser await the final touch — a tiger to represent the squadrons that flew the Sabre.(ABC Mildura-Swan Hill: Jennifer Douglas) Fighter in a sorry state Despite a few missing pieces, namely the wings and cockpit cover, volunteer Greg Wood is proud of how far the project has come. "It was in a fairly basic state when it arrived here in pieces," he said. "It had been dismantled completely. You pretty much couldn't have taken much more off it." The restoration is a collaboration between the Dareton Men's Shed, the Mildura RAAF Memorial and Museum, and the Mildura RSL. The huge undertaking began when local philanthropist and RAAF historian John McLaughlin made a winning blind bid for the warbird at an Australian National Aviation Museum aircraft auction. "I was pleased to have won the bid for the CA-27 Sabre," Mr McLaughlin said. "It was certainly a leap of faith, but my hope is that it will be part of a permanent static aircraft display at Mildura's RAAF museum." The CA-27 Sabre's restored canopy is nearly complete after being used as a rabbit hutch for many years.(Supplied: Greg Wood) Parts of several Sabres have been sourced for the restoration, including a replacement for the perspex canopy that was broken during a pilot ejection. Phil Roeszler is a retired motor mechanic who was tasked with the canopy restoration. "The original canopy had been in a wreck where the pilot had ejected, but the canopy didn't, so he actually went through the canopy and amazingly survived," he said. Mr Roeszler was able to find another canopy that had been used as a rabbit hutch. It has taken hours of polishing, but it is almost finished. Phil Roeszler and the Sabre's restoration team have dedicated hours of polishing to restore the canopy.(ABC Mildura-Swan Hill: Jennifer Douglas) A piece of the Cold War The Sabre's link to Mildura's wartime service is through the World War II air force training base, the Mildura Operational Training Unit (2OTU). After the end of WWII, the unit relocated to Williamtown air base at Newcastle, NSW and in 1952 reformed to begin training fighter jet pilots. The squadron changed its name to 2OCU, or Operational Conversion Unit. The CA-27 Sabre was Australia's first fighter jet able to travel at supersonic speeds, and provided frontline single-seat fighter aircraft defence in the 1950s and 1960s. Several major parts of the restored Sabre served in Australia's Cold War efforts with the 77th and 79th Squadrons at Butterworth air base, Malaysia, and at the Ubon air base in Thailand. The planes were deployed as part of Australia's South-East Asia Treaty Organisation, mobilised to defend Thailand against attack from its Communist neighbours. Sabre's final landing The restoration team is hard at work on the final phase of the static Sabre display, drilling thousands of wing rivets to repair extensive damage to the wings and undercarriage. Repairs to the Sabre's damaged wings required thousands of rivets to be replaced.(ABC Mildura-Swan Hill: Jennifer Douglas) Paul Mensch from the Mildura RSL Sub Branch said he was impressed with the progress of the restoration so far. “It’s all credit to the thousands of years of combined expertise provided by the men's shed volunteers that have made this restoration such a success," he said. "It's going to be a fantastic asset to the Mildura RAAF Memorial and Museum and a great drawcard to tell Mildura's wartime history."2 points

-

Bundaberg’s Jabiru Aircraft has created face shields with the help of 3D printing to provide extra protection for frontline workers dealing with Covid-19 cases. Bundaberg’s Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd, whose business usually focuses on producing light sport aircraft and engines, has responded to the current pandemic crisis by creating face shields utilising 3D printing technology to provide extra protection to frontline health workers dealing with Covid-19 cases. With these efforts Jabiru Aircraft joins other manufacturing entities and individuals around the world in producing emergency Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during a time of global shortage. Jabiru Aircraft Business Manager Sue Woods said last Friday she and an employee, engineer Alex Swan, were looking at ways to support health care workers during the current public health situation, and with a little ingenuity and the help of a 3D printer they were able to design and commence the manufacture of the PPE. Sue said they were very concerned for the wellbeing of paramedics, GPs and medical personnel who were most at risk of contracting the virus. They hoped the extra layer of protection offered by the face shield would keep these essential people healthy. Both Sue and Alex have family members who work in healthcare, and they were on the same path of thinking – wanting to ensure not only their loved ones stayed safe, but also others facing the Coronavirus firsthand. 3D printers used to create face shields “I came to work one day after watching footage on the shortage of PPE and thought ‘what can we do'?” Sue said. “Alex experimented with cutting the visor section until we had the right shape and he modified the headband 3D file to accommodate glasses underneath. “We then had both a local dentist and a local doctor try the face shields, and check with sterilising products, and we had good response.” Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd has designed and manufactured emergency Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during a time of global shortage in result of the Covid-19 situation. Two 3D printers are used by Jabiru Aircraft to create the head band for the face shield and the transparent polycarbonate for the visor is cut to shape with a flatbed CNC router. “Our engineer Alex Swan has been very motivated with this project and volunteered much of his own time, getting up in the middle of the night to keep the 3D printers going 24/7,” Sue said. “We have two 3D printers and Alex took them home so he could get up at 2am to press the button to start the next headband.” Sue said it took less than a week to develop the idea and start production of the face shields, and they hope to have 100 finished and shipped to paramedics in Western Australia by Monday. She said the slowest part of the production was the 3D printing and she was thankful for the support from other local organisations who offered assistance. “To increase our production rate of the 3D printed component, CQUniversity Bundaberg and Gladstone and Makerspace Bundaberg and Hervey Bay, along with CQUniversity Makerspace have jumped on board very quickly, and we now have several additional 3D printers in action,” she said. “We are also getting offers of assistance from schools in the local community.”2 points

-

They finally cracked it!! It's here!!!! The flying dunny!!!! 😃 https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1ED1qjUUHv/1 point

-

It wasn't until he moved near to an airfield in the UK over a decade ago that mechanical engineer Ashok Aliseril Thamarakshan began to seriously consider learning to fly a plane. He got his first taste of flying a few years later, when his wife Abhilasha bought him a 30-minute flight experience for his birthday. Aliseril, who is based in Essex, England, booked in some flying lessons at a local airfield and flew to the Isle of Wight, an island off the English south coast, during his first session. Aliseril got his private pilot's license in 2019 . (Ashok Thamarakshan via CNN) "That was quite an eye-opener into how (flying) gives you the freedom to just go places if you have that ability, and access to an aircraft," he tells CNN Travel. "So that really got me hooked." Aliseril got his private pilot's license in 2019 and soon began hiring planes for short flights. Amateur build But as his family grew – he and Abhilasha now have two daughters – the two-seater planes typically available for private hire became even less suitable, and he began to mull over the idea of buying his own plane. Aliseril briefly considered buying an older aircraft, and looked at some that had been built in the 1960s and 1970s. However, he says he felt uneasy about the prospect of flying his family in an older aircraft that he wasn't familiar with, and didn't think it would be a "comfortable journey." Aliseril began to look into the possibility of building a plane himself, reasoning that this would allow him to gain a better understanding of the aircraft so that it would be easier to maintain in the long term. After researching self-assembly aircraft kits, he came across a four-seater plane manufactured by South African company Sling Aircraft that ticked all the right boxes. In January 2020, Aliseril flew to the Sling Aircraft factory facility in Johannesburg for the weekend in order to take the Sling TSi aircraft on a test flight and was so impressed that he decided to purchase it. "This was pre-Covid, where travel was still very easy at the time," he explains. "I ordered the first kit when I got back. And by the time it arrived, the UK was in full lockdown." Aliseril says his colleagues, some of whom had experience with building aircraft, initially offered to help with the build. But the restrictions brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic, which had spread across the world by this point, meant that this wasn't possible. He enlisted his daughters to help. (Supplied/Ashok Thamarakshan) Undeterred, he constructed a small shed in his back garden and planned out the different stages of the project, which would be monitored by the Light Aircraft Association, a UK representative body that oversees the construction and maintenance of home-built aircraft, under an approval from the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). The rules for amateur built aircraft differ slightly from country to country. In the US, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has an experimental airworthiness category where special airworthiness certificates can be issued to kit-built aircraft. Amateur-built airplanes in the UK are investigated by the CAA, who will issue a "Permit to Fly" once satisfied that the aircraft is fit to fly. Although the start of the build was delayed slightly due to the Covid-19 restrictions in place in the UK at the time – the Light Aircraft Association inspector assigned to the project was required to visit his working space beforehand – Aliseril was able to begin in April 2020. While he notes that his engineering background helped in some ways, he believes that it was actually his home improvement experience that proved most useful while constructing the aircraft, which has a length of 7.175 meters and a height of 2.45 meters. "These aircraft kits are designed for any amateur to build, provided you're a bit hands-on and you've got experience working with some specialist tools," he adds, describing the detailed "Ikea furniture type instructions" with drawings that came with the kit. "I would say generally, anyone can get involved in these sorts of builds." Aliseril completed the work himself, drafting in Abhilasha to assist with some of the sections that required more than one pair of hands. Their eldest daughter Tara, now nine, was on hand for tasks such as removing the plastic from each of the components. By the end of summer 2020, Aliseril had built the tail and the wings. He began constructing the fuselage section in October, when the next part of the kit arrived. Although he'd initially planned to hire a workshop to construct the aircraft, Aliseril feels that creating a workspace at his home was the better choice. He constructed a small shed in his back garden and planned out the different stages of the project. (Supplied/Ashok Thamarakshan) "I could just step into the shed and work on it," he says. "So having everything just in the back garden really helped, even though space was tight." Each stage of the project had to be signed off by an inspector before he could move onto the next task – the Light Aircraft Association completed around 12 inspections in total. Once the majority of the components were constructed, and it was time to put the aircraft together, Aliseril moved everything from his home to a hangar near Cambridge for the final assembly and engine fit. The aircraft passed its final inspection a few months later. It was one of the first Sling TSi homebuilt aircraft constructed in the UK. G-Diya, named after his youngest daughter, was signed off for its first flight in January 2022. Aliseril recalls waiting on the ground anxiously as a test pilot took the plane he'd spent 18 months building up into the air. "He took it up for about 20 minutes, and then he came back," he says. "It was a big relief. I couldn't lift my head up to see what was happening (during the test flight)." That first flight was hugely significant in many ways. "With these build projects, everyone calls it a project until it's first flown," he explains. "Once it's flown, it's always called an aircraft. You never call it a project anymore. That's psychologically a big step." When it was time to fly the aircraft for the first time himself, Aliseril was accompanied by another experienced test pilot. While he admits to being decidedly cautious, the test pilot was "throwing the aircraft about as if it was a racing car." G-Diya has a range of 1,389 kilometres. (Supplied/Ashok Thamarakshan) "I was feeling very nervous, I didn't want to put any extra stress on it," Aliseril explains. "But (the test pilot) was really pushing it to the limits. And it was good to experience that. I know that (the aircraft) can handle this much. "Once I landed, (the test pilot) clapped his hands and said 'Congratulations, you've just landed the plane you built.' That was a great feeling." G-Diya, which has a range of 1,389 kilometres, went through a number of further test flights before it was issued with a permit to fly in May 2022. The following weekend, Aliseril flew with his wife and daughters Diya and Tara, five, to the Isle of Wight, where they took a short taxi ride from the airfield to the beach. "The kids were really happy," he says. "So that sort of freedom. And the fact that we could just do that on a Saturday and still be back by 4 p.m. That was a great feeling." They continued taking trips together within the UK, flying to Skegness, a seaside town in eastern England and the village of Turweston in Buckinghamshire, before Aliseril felt comfortable enough to take them a little further afield. Last Easter, the family, who've been documenting their trips on their Instagram account, fly_home_or_away, travelled to Bergerac, France, which Aliseril describes as their "most memorable" trip together. According to Aliseril, G-Diya has flown over 300 hours in the past two years, travelling as far as Norway. The family have been documenting their trips on their Instagram account. (Ashok Thamarakshan via CNN) Family trips For Aliseril, one of the main benefits of the plane, aside from the freedom it provides him and his family, is the friendships he's formed with other pilots. He was always mindful that owning an aircraft could become a financial burden, but has been able to get round this by working out an arrangement to share it with three others. "To get your private license, it costs quite a bit," he adds, before noting that many of those who've taken on similar projects are either retired, or are people "who have the time and financial status" to fund the process. "I kind of knew that from the beginning, and thought I'd take that risk and try to do it myself," he says. "I knew that once it was done, I would easily be able to find people to share that cost. And it's worked out quite well (for me)." "It becomes a communal thing," he says. "You always have somebody to fly with if your family is not available. Also, having other pilots who are friends – you learn from each other."1 point

-

As the famous saying goes, you only get one chance to make a first impression. By the end of 2023, ultralight eVTOLs like the Lift Hexa and Ryse Recon will be in the air, and with that, eVTOLs will be introduced in the U.S. for the first time in history. This first impression will resonate for years to come and hopefully, only in positive ways. Ultralight eVTOL developers like Ryse Aero believe this aircraft type will allow the industry to “crawl, walk, and then run,” helping to familiarize the public with this novel aircraft. Ryse Aero Photo “Beyond military use and first responder applications, we plan to make Hexa available around the country for people to experience eVTOLs for themselves, starting this year. We also plan to set up permanent flight locations,” said Kevin Rustagi, a spokesperson and director of business development at Lift. “We’ve already presold 4,000 tickets [$249 each] for a series of short flights along with VR simulator training. Having flown Hexa, I can say that it’s incredibly fun.” Lift’s customers will go through a three-part simulator training and then three actual flights with a dedicated instructor in constant communication. The first flight, for example, encompasses auto-takeoff, climbing vertically to about 15 feet (five meters) and then landing using auto-land. “The more people become familiar with eVTOL aircraft, the more open they’ll be,” Rustagi said. “People saw Anderson Cooper fly a Hexa on 60 Minutes, but it will be different for people to see it in person and fly one themselves.” “We’re all about making eVTOL flight accessible to everyone,” added Balazs Kerulo, chief engineer and lead designer at Lift. “The earlier ultralight companies like Lift start flying, the earlier we can garner public acceptance for the industry as a whole. ‘Flying cars’ have been discussed since cars first arrived, so it’s not a new concept. What’s new is that ‘flying cars’ are real.” Beyond military and first responder applications, Lift Aircraft plans to make its Hexa eVTOL aircraft available around the country for people to experience eVTOLs for themselves. U.S. Air Force / Samuel King Jr. Photo Anticipating perception Most in the eVTOL industry already realize that this will be the introduction of eVTOLs to the U.S. market — watching others fly small one-person ultralight eVTOLs and/or actually flying one — and that it’s going to happen very soon. As mentioned, from the overall public perception of the eVTOL industry, there’s a lot riding on the launch of ultralight eVTOLs. This includes perceptions of safety, of course, but also noise and more. One question is whether the public will see these small aircraft flying around and view eVTOLs in general as financially unattainable. “There may be a perception among some that they could only be for the rich,” said Erik Stephansen, vice president of regulatory affairs and aerodynamics at Ryse. “But we are going to launch with a price that’s about one-tenth of a helicopter, which makes it possible for many more people to own one.” This is still not affordable for the everyday person, of course, but that’s always been the case with ultralight aircraft. “We will be selling to private owners and are making test flights available to potential customers,” Stephansen said. “There will be those who want solely the adventure of private flight, but we already have many customers who have preordered who own farmland and ranchland. An ultralight eVTOL allows you to go as the crow flies, and do tasks very efficiently. We have more demand than we can fill through to the end of 2024 already.” He added that “ultralight eVTOLs are a great place to start eVTOL flight. They will allow the industry to crawl, walk and then run. Being at shows like CES in Las Vegas — we were the first to fly there — has also helped with familiarization of the public. We will continue to be at events this year.” With six independent propulsion systems and an independent, removable battery, the Ryse Recon is targeting a range of up to 25 miles (40 kilometers), and top speeds of 63 miles per hour (100 kilometers per hour), while flying 400 feet (120 meters) from the ground and carrying a weight of 200 pounds (90 kilograms). Ryse Aero Photo Emergency use Perceptions that eVTOLs are only for the rich and have no benefit to society may be negated by the plans of ultralight eVTOL firms like Lift to introduce emergency response uses right away. This may help the public understand the even broader range of uses that will come when larger type-certified (TC) eVTOLs are introduced in the U.S. — several months later in 2025. “For emergency response, there are a variety of eVTOL use cases for ultralights and TC aircraft alike,” Kerulo said. “A paramedic could fly Hexa to the scene of an emergency, quickly and above traffic, to stabilize a patient. From there, they could send the patient back to the hospital in Hexa, flown remotely. Water rescue, manned/unmanned teaming, search-and-rescue — there are literally hundreds of use cases.” Many companies introducing TC eVTOLs are preparing use case demonstrations and other public awareness activities for their larger aircraft that will coincide with — or will follow — the launch of ultralight eVTOLs. For example, the two-seat VoloCity from Volocopter, now in the process of obtaining European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) certification, will be taking center stage at the 2024 Olympics in Paris. In EASA’s study on the social acceptance of urban air mobility in Europe, the agency identified Paris as the most promising city for airport shuttle and sightseeing use of eVTOL aircraft. Lift plans to set up permanent flight locations around the U.S., and has already presold 4,000 tickets for a series of short flights using its Hexa eVTOL aircraft, along with VR simulator training. U.S. Air Force / Samuel King Jr. Photo Regulatory change? No eVTOL company, whether ultralight or TC, wants an accident. From Lift’s perspective, Kerulo noted that “the fear is that a flight incident would set the industry back, and so it’s paramount that we all remain safety-focused.” Rustagi added, “We’re rooting for our competitors. The market is immense. We want the pioneers to do well, to survive and thrive, to lay the foundations for the industry.” Stephansen had similar thoughts. “We are all in this together,” he said, adding that electric propulsion provides extra redundancies. Operationally, there are also safety features in eVTOLs such as auto-land and auto-takeoff. And in the Recon, for example, if you let go of the controls, it just hovers. “There are so many safety features,” Stephensen said. “Having said that, I do think true and full acceptance of the safety of eVTOLs will come later, from the operation of the larger eVTOLs as they’ll be flying over cities.” To make the Ryse Recon more affordable, Ryse Aero plans to launch its eVTOL aircraft with a price that’s about one-tenth of a helicopter. Ryse Aero Photo But to perhaps add extra assurance that there are no accidents with the first wave of eVTOLs to fly — that is, the ultralights — should a set of minimum safety features be mandated in ultralight design under the U.S. ultralight regulations (Part 103)? And should restrictions in this regulation pertaining to where people can fly an ultralight and at what speed and altitude be updated with the arrival (and expected large volume) of ultralight eVTOLs? Tom Charpentier, government relations director at the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), described 103 as “a very unique and limiting rule.” “To the question that’s been asked over the years of whether it should be changed, our answer is always no,” he said. “It will lose its regulatory uniqueness and changing it would risk losing the operational freedom that Part 103 allows. The FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] will find a way to regulate ultralight eVTOL use to a level it feels protects public safety.” Rob Hackman, EAA vice president of government affairs, noted that developing standards and regulations for eVTOL aircraft and operations is taking some time, but the FAA and industry need to get it right. “The FAA gets criticized for moving slowly, but operating in the national airspace system, a system already utilized by many different aircraft and pilots, is a very complex issue,” he said. “Just like operating on roads and highways, when piloting an aircraft, everyone needs a thorough understanding of the operating rules and how to operate safely, no matter what type of machine they are piloting.” Lift’s Hexa eVTOL aircraft is a multirotor vehicle with 18 sets of propellers, motors, and batteries. U.S. Air Force / Samuel King Jr. Photo For his part, Stephansen describes Part 103 as “very solid but also left open for interpretation.” “It has allowed for thousands of different ultralights to come to market and be flown safely since the regulation was created in the 1980s,” he explained. “Partly because of the regulatory openness, thus, allowing for new safety innovations, ultralight is a very safe aircraft category. Part 103 ensures safety, limits risks, and supports personal flying freedoms. I think it strikes a really good balance between these. When you think about it, it’s quite amazing that a framework from the 80s is still applicable today. It’s got a proven track record.” Hackman adds that the EAA and others also have a strong history of spending a lot of time educating ultralight aircraft operators about the laws on how and where they can operate, as well as the importance of “fly friendly” practices and respect for the non-flying public. “Hopefully, this philosophy will continue with ultralight eVTOL use,” he said. “This will be an important part of public acceptance, along with safety.”1 point

-

We ran through an “Airplane!” scenario with the aviation department at the University of North Dakota file_1280x720-2000-v3_1.mp4 Less than a minute into a flight to Omaha, alarms started blaring. From the cockpit, the pilot uttered one worrisome word: “Yikes.” He gripped the side stick, unwittingly disengaging the autopilot, and the plane shot into the clouds. It was a dangerous maneuver for any flight crew member, especially one without any experience. “I have no clue what’s going on,” said Brett Daku, his voice barely registering over the din. Suddenly, WAPO Flight 123 fell silent. Help was on the way. Nick Wilson, an associate professor of aviation at the University of North Dakota, appeared from what would have been first class had we been flying a real plane. He approached the 19-year-old finance major and explained what had happened. “A high-altitude stall is a dramatic event and is broadly avoided,” Wilson said. “You can’t recover from it.” Unless, of course, you are in a flight simulator. Unlike real life, the high-tech training device that replicates the mechanics and challenges of flying has a reset button. It also does not judge or cause harm, except to your ego. In March, we published an article about surveys that showed many Americans think they could land a plane if they had to step in for a commercial pilot. Pilots and aviation experts were less sanguine, though they didn’t outright dismiss the idea. Brett Venhuizen, professor of aviation and chair of the aviation department at the University of North Dakota, in Grand Forks, suggested a way to test the aspirational pilots’ bravado: Stick them in one of the school’s flight simulators. Patrick Miller, a participant in the simulator test at the University of Dakota in Grand Forks, has never flown a plane before. (Andrea Sachs/The Washington Post) Setting up the simulator test At the university’s John D. Odegard School of Aerospace Sciences, students pursuing their pilot’s license log hours in the virtual reality machines. As commercial airline pilots, they will earn their type-rating certification on simulators modeled after specific aircraft. Every six months, they must demonstrate their capabilities to the airline through practice runs in a simulator. For our simulation modeled after an Airbus A320, which typically seats 140 to 170 passengers, our recruits had one objective: to successfully land the aircraft and save everyone onboard. Venhuizen was in charge of rounding up the participants. He chose four men and two women, ages 19 to 67. Four people had zero pilot experience. However, three members of the group (Patrick Miller, Meloney Linder and Daku) had played around with flight simulators and one (Alexa Vilven) had watched YouTube videos of pilots landing planes. We also had two pilots on board: Aaron Prestbo, a physician and recreational pilot from South Dakota, and Brian Dilse, a former airline pilot who worked for a major carrier in Dubai and now teaches at UND. Each participant was separated from the group until their turn, so no one could pick up any tips through observation. At the start of the exercise, Wilson handed each person a boarding pass (Washington Post Airways Flight 123 from Duluth, Minn., to Omaha, a 90-minute flight) and described the scenario: The aircraft’s two pilots were incapacitated for unexplained reasons, and the passenger would have to guide the plane to safety using all the tools available on the flight deck. For the sake of time, he said we would hopscotch over a few steps, such as accessing the code to the locked cockpit, removing the pilots’ bodies and adjusting the seat. He dropped an important hint: The pilots may or may not have been wearing some type of head gear. He was referring to the headset, an essential piece of equipment for communicating with ground personnel. Everyone entered the scene at the same point in the flight and with identical conditions. The plane was flying level at 20,000 feet, with overcast skies at 1,000 feet, calm winds and no rain in the forecast. The sky was eerily empty. And with that, Wilson wished the pilots good luck. How the novices did in the simulator Unlike nearly a third of the respondents in a YouGov survey from January, none of the novice pilots in our experiment claimed to be confident they could land a plane. Miller, a 67-year-old communications editor at UND, said his interest in World War II plane simulators might help, but he worried that he would crumble during landing. When asked if he would jump up to assist in an emergency, Daku, the college student, said he would see if another passenger would volunteer first. If no one did, he’d step in with low expectations. “Probably I will end up crashing the plane,” he said, “but who knows?” Miller was the first to fly and he immediately started asking questions, even though he had not put on the headset. Wilson and Matt Opsahl, a UND instructor, broke scene to reply. Eventually, they ceased all communication. “You’re not answering any of my questions,” Miller said, as he squinted at the primary flight display. “I’m fully on my own.” Miller porpoised through the clouds, ascending and descending several thousand feet. Thankfully, the simulator didn’t have the full motion feature, or at least one of us would have needed a bucket. Alarms shrilled and chirped after he disengaged the autopilot and hit the service ceiling, preventing the plane from flying any higher. Wilson entered the cockpit with the bemused-but-patient expression of a pee-wee coach. “This could go on for as long as we have fuel,” he said, “which could be four or five hours.” To move the test along, the instructors programmed the coordinates to the Minneapolis airport, the site of our emergency landing. Below, the flat Midwestern landscape fanned out to the fake horizon. Miller switched to manual and the plane wobbled like a baby bird thrown from its nest. The aircraft thumped to the ground but continued to roll over another runway and into what appeared to be a field. “It’s unlikely that the gear would be intact,” Wilson said. But on the bright side: We would have all survived. Result: Success Meloney Linder takes a seat in the flight simulator. (Andrea Sachs/The Washington Post) Linder, a 51-year-old vice president of communications and marketing for UND, made several smart decisions from the get-go, such as slipping on the headset and, for the most part, remembering to press the radio transmitter button when speaking. “WAPO123, this is Minneapolis ATC,” Opsahl said in his role as an air traffic controller. “We noticed that your altitude is deviating a lot. If you’re on comms, respond please.” She also made several mistakes, including a biggie that ended the game. “Oh, crap!” she exclaimed when an automated message warned, “Stall, stall, stall.” “I’m crashing.” In addition to deactivating the autopilot, Linder stalled, meaning the wings can no longer produce a lift, and banked, or caused the aircraft to list to one side — a hopeless situation. “I have so much respect for my pilots right now,” she said. Result: Fail Watching YouTube tutorials paid off for Vilven, a 31-year-old accountant for the university. Without missing a beat, she reached for the headset and called for help. Air Traffic Control: “Is there an emergency?” Vilven: “I believe so.” Air Traffic Control: “Are you able to fly the aircraft?” Vilven: “Uh, no.” Air Traffic Control: “WAPO123, we’re going to do our best to help you.” Vilven: “Gotcha.” Opsahl and Wilson, who was pretending to be a pilot sharing the same airspace, provided Vilven with the altitudes and air speeds needed to approach the Minneapolis runway. With their guidance, she lowered the flaps to slow the aircraft and dropped the landing gear. When she was within shouting distance of the runway, they advised her to deactivate autopilot. “I think I’m too high,” she said, as she missed the runway and the plane started to ascend. “I’m going up. I’m in the clouds.” A warning system activated: “Bank, bank, bank.” Air Traffic Control: “We don’t know what WAPO is doing.” Result: Fail Brian Dilse, a commercial airline pilot who teaches at UND, was a pro in the cockpit. (Andrea Sachs/The Washington Post) How the recreational pilot did in the simulator Before entering the simulator, Prestbo, a 47-year-old physician, said he would volunteer to land a plane in emergency, just as he would raise his hand to help an ill passenger. But he had a few concerns, which he later admitted had caused his leg to shake inside the simulator. “I am more confident about flying versus landing,” said Prestbo, who earned his private pilot’s certificate in 1997 and flies single-engine planes for fun. He was also worried about the unfamiliar dials, switches and levers in the cockpit. “This is out of my comfort zone,” he said as searched the panel for the radio. Luckily, he found it and connected with air traffic control and the other pilot. The pair fed him information each step of the way. Less than a half-hour into the flight, the sky started to brighten and the ground materialized below. A few miles from the runway, he disconnected the autopilot. “Okay, I have control, such that it is,” he said. “It’s real now.” The plane swayed slightly, but two minutes later, it was solidly on the ground. It took much longer for his leg to relax. Result: Success How the commercial pilot did in the simulator Dilse, who has cargo and passenger flight experience, was the one participant who had every right to be confident. And yet he wasn’t. When presented with the imaginary scenario, the 39-year-old responded, “Hopefully there is someone that actually worked for the airline and was more experienced than me with the airline. I’m not going to be the first one to jump and say, ‘I’m here to save the day.’ I’m not going to be a superhero.” He was also uncomfortable with the idea of flying solo. “You need two pilots to operate this aircraft,” he said. “So when you ask if I feel confident, I’d be lying if I said yes.” Even so, he approached the mission with a high level of professionalism and self-possession. He practiced the guiding principles of flying — aviate, navigate and communicate — and followed the advice of a British Airways instructor who recommends taking five seconds to sip “your tea” to avoid making any rash decisions. Dilse’s advanced aviation skills allowed him to tap into the plane’s sophisticated navigational and technical systems. Unlike the other pilots, he also considered a multitude of factors that could influence the outcome, such as the amount of fuel, the weather at the Minneapolis and Omaha airports, and the maximum landing weight. For his own safety, he wondered what had caused the pilots to fall ill. Depending on the answer, he might need to wear a gas mask or avoid the chicken entree. He also requested medical services to meet the plane on the runway. When he could see the ground, he set the autobrake and informed air traffic control that he could take it from here. “I’m pretty comfortable with what’s happening now,” he said. Dilse landed the plane as smoothly as a butterfly alighting on a leaf. He stopped the aircraft and cut the engines. Then he activated the PA system and spoke to the passengers. “Ladies and gentleman,” he said calmly, “everyone please remain seated.” Result: Success Takeaways from the simulations Based on our simulator experiment, no inexperienced traveler should ever volunteer to land a plane in an emergency. Even with a prodigious amount of guidance, which Wilson said was highly improbable in a real-life scenario, our recruits still cratered. However, if there are no other options, remember these invaluable lessons. Never disengage the autopilot (don’t move the side stick or press the red button). Put on the headsets and hold the switch when you speak. And take five seconds to sip your proverbial tea. The private pilot, who flew the plane with a clear head, deft hand and trembling leg, surprised the experts. “I didn’t think it was gonna go that well at all,” Opsahl said. As expected, the former airline pilot aced the test. “He did all the things that you would expect a professional aviator to do,” Wilson said, “and that led to a successful, honestly, relatively boring sequence of events compared to our other participants.” In the event of an airplane emergency, we can all hope for boring.1 point

-

Tucked away inside a small north Queensland hangar are two planes that belong to a bygone era, flown by men with a deep appreciation of the past. With their bright retro colours and open cockpits, the World War II-era Tiger Moth biplanes almost look out of place in modern-day Mackay. They have been kept in pristine condition by the sons of Fred Christiansen, who once used them to ready fighter pilots for combat. Before and after the war, Mr Christensen worked in the sugar cane industry around Mackay, and he eventually settled in the "sugar city". He also passed on his love of flying to his two sons. One of them, Greg Christensen, 69, a founder of the Mackay Tiger Moth Museum and himself a pilot, recently reluctantly hung up his pilot's cap and goggles. But he's urging others to get involved, saying it's important to many descendants of local war veterans to preserve these moving memories of their past. "There's other blokes that are quite a bit older — a couple of guys are in their 70s," he said. "That is the only volunteer-based museum [housing Tiger Moths] where there's no profit going to... the pilots and the ground crew." As well as preserving the air crafts and their history, the Mackay Tiger Moth Museum has given passengers a unique glimpse of Mackay through an open cockpit.(Supplied: Mackay Tiger Moth Museum) WWII training aircraft The De Havilland Tiger Moth was first manufactured in the United Kingdom in 1931. During World War II, Tiger Moths were used as military training aircraft in Commonwealth countries, including Australia. According to the Royal Australian Navy, almost 1,100 of the planes were build in Australia between 1940 and 1945. The two Tiger Moths were purchased by the museum in the 1970s, to prevent them being sold overseas. The Tiger Moth Museum has been run by volunteer crew and pilots for decades.(Supplied: Mackay Tiger Moth Museum) Mr Christensen flew them for about 40 years. "My father was an instructor during the war, teaching people to fly in Tiger Moths. "My brother... was our first chief pilot and he taught most of us to fly the Tiger Moths." Mr Christensen completed his last flight in recent months, before moving south to be with family. "I did in excess of 1,500 joy flights around the town, so I got to see a fair bit," he said. He made sure his final passenger was someone special. "My wife was onboard. [She] was looking after the kids while I was playing with those things. It was quite nostalgic," he said. WWII descendants among museum pilots The Tiger Moths have been a common sight in Mackay's skies for more than 40 years.(Supplied: Mackay Tiger Moth Museum) Many volunteers and pilots at the Mackay Tiger Moth Museum are descendants of WWII veterans. Mr Christensen now hopes younger pilots will step up to the controls. "The aeroplanes are in great nick...[they] will outlast the people," he said. "It'd be great to see the younger people get enthused and get as much out of it as we have. One of the museum's Tiger Moths was built in 1943 and the other in 1942. Both have undergone expensive repairs and refurbishments over the years. The team of volunteers sells joyrides, with the proceeds invested in maintenance of the planes. Mr Christensen said the historic aircraft had long surpassed people's expectations and would still be gracing Mackay's skies for a long time to come. "They were supposed to go five years. That's what their life expectancy was," he said. "They'll go on forever."1 point

-

One of the world's rarest planes has made its final flight, touching down in a western Victorian town that fundraised for two years to bring it home. The Australian-made Wirraway was used to train pilots at the Nhill airbase during World War II. At its peak, there were as many Royal Australian Air Force personnel at the airbase as the population of Nhill. Today the population of Nhill, which is halfway between Melbourne and Adelaide, is about the same at just 2,000. The plane is made up of parts from countless discarded Wirraways, and is among the best preserved in the world. Aircraft engineer Borg Sorensen spent 10 years scouring the country for the parts, and another eight putting the pieces back together. He found his first Wirraway in Horsham, an hour from Nhill, hacked apart with an axe and spread over five paddocks. The Wirraway is welcomed by a large crowd at the Nhill Aerodrome.(ABC TV) Community funding brings plane home On Saturday Mr Sorensen flew the historic aircraft for the last time, from Frankston to the Nhill Aerodrome. "It was the first production-built aeroplane in Australia," Mr Sorensen said. "I wanted it preserved. I built it to preserve a Wirraway because there are not many left." The Wirraway was used to train Royal Australian Air Force pilots at the Nhill airbase during World War II.(Supplied: Nhill Aviation Heritage Centre) The community met its $300,000 fundraising target just hours before the plane touched down. Nhill Aviation Heritage Centre president Rob Lynch said the support for the project had been unprecedented. The project is entirely community funded. Weeks out from the landing an anonymous donation of $15,000 was received. It is hoped having the aircraft at the base will help commemorate the men who trained at Nhill and died at war. Construction underway at the Royal Australian Air Force Base at Nhill in 1941.(Supplied: Nhill Aviation Heritage Centre) Mr Sorensen could have sold his Wirraway for almost twice as much on the international market, but he knew it belonged at Nhill. "We'd been flying it for 16 years, my son and I, and we started going round doing airshows and then all of a sudden I thought 'That's really not what I built it for'," he said. "My reason for building it was to preserve it and when they put it to me, would I consider selling it, I thought 'Yes, that will just suit me fine'." Max Carland flew Wirraways during his training in the air force.(ABC Western Vic: Jessica Black) 'Amazing to see the thing still working' Max Carland flew fighter planes in New Guinea in World War II and came of fighting age with the Nhill airbase on his doorstep. "Most of the people at Nhill joined the air force because there was an air force stationed here," he said. "Having flown the Wirraway during my training days, it's amazing to see the thing still working." But the Wirraway was not without its faults. "Another thing it used to do that we didn't like very much was it used to, on starting, sometimes the engine would catch alight, so every time we started a Wirraway engine, we had to have a big fire extinguisher." Merv Schneider was a radio navigator and trained at the Nhill airbase before he was old enough to serve. "Our fighter pilots were Wirraway-trained. Being built in Australia, the opportunity of one coming home to Nhill really brings home the significance of the Wirraway."1 point

-

On June 30, 1943, Flight Sergeant Colin Duncan and his squadron of Spitfires took off on a mission to intercept Japanese aircraft over Darwin. But while the ensuing battle has for decades been marked in folklore, the whereabouts of Duncan's shot-down plane has, until now, remained a mystery. The Spitfire A58-2 Duncan was flying caught fire, engulfing the cabin in flames and sending the aircraft plummeting towards the ground in a spiral dive. Desperate to escape, the rip cord to release his aircraft canopy failed, leaving Duncan scrambling to force it off and struggle out of the aircraft to parachute to the ground. Flight Sergeant Colin Duncan defied death to make it back to Darwin.(Supplied: Australian War Memorial) But his battle was only just beginning. Duncan was stranded with severe burns in tough Top End terrain, alone and with minimal supplies, and it would be another five days before he was rescued. Bombing of Darwin: 70 years on On February 19, 1942, Japanese forces launched air raids on Darwin. Hundreds were killed in the attack. This compilation of videos, pictures and recollections take a look a of the most significant moments in Australian history. Seventy-six years since that fateful flight, Colin Duncan's grandson has visited the wreckage of his grandfather's plane for the first time. As he walked through the untouched debris of the Spitfire's final resting place, Duncan Williams was left shocked. "It's a genuine time capsule," he said. "I didn't expect it. I don't know what I was expecting really. Mr Williams said he was amazed his grandfather managed to escape alive. On viewing the wreckage, he remarked on how the Spitfire hit the ground with such force it left only a mangled mess of metal. "He was very lucky to get out alive," Mr Williams said. "Here we've got the cannons. You can see the angle the plane hit the ground. The aircraft wreck is now protected under the Northern Territory Heritage Act.(ABC News: Ian Redfearn) The remote location in Litchfield National Park, about 110 kilometres south of Darwin, means the Spitfire has remained undiscovered until recently. And with the crash site immensely difficult to reach and only accessible by helicopter, the plan is to preserve the wreckage at its final resting place. 'This is our Pearl Harbour' The RAAF has handed ownership of the wreckage to the Northern Territory Government in the hope it will help tell the story of Darwin's role in World War II. According to RAAF Air Commodore John Meier, the new find in the Top End outback is testament to the Darwin's often forgotten place in modern wartime history. Hundreds were killed in air battles over Darwin during World War II.(ABC News: Ian Redfearn) "We only had a few Spitfires in Australia, and this one is of major significance because it was lost in the battle of Darwin," he said. "If you compare it to Pearl Harbour, that everyone knows about, this is our Pearl Harbour, and it's not particularly well known by the Australian population." Colin Duncan continued flying Spitfires in the war, and later played cricket for Victoria as well as running a successful building company. He died in 1992 from cancer, leaving behind his wife and two daughters.1 point

-

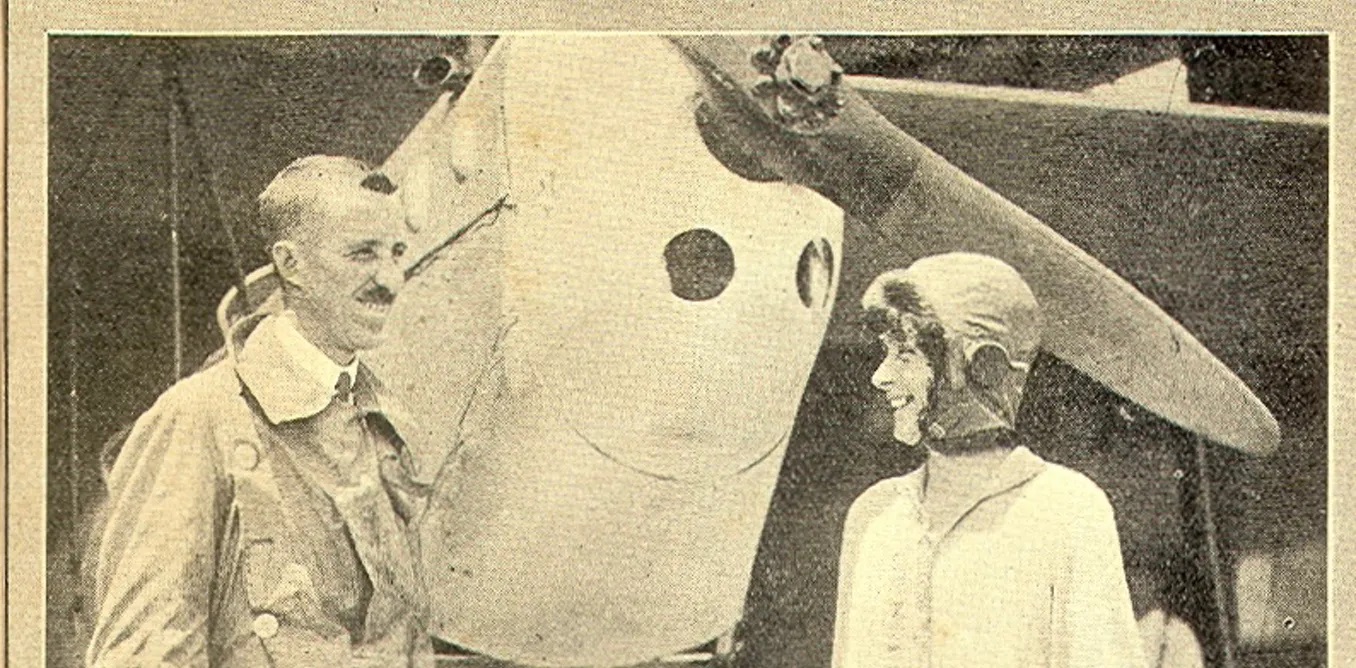

Before the glamorous flyers of the 1930s like Amelia Earhart, “Chubby” Miller and Nancy Bird Walton, another woman opened the way to the skies — and were it not for a tragic twist of fate, her name might now be just as familiar. Her name was Millicent Maude Bryant, and in early 1927, she became the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia. She was also first in the Commonwealth outside Britain. Millicent Bryant c.1919. Portrait by Monte Luke. Author provided A boundary-pusher who met an untimely end Millicent was born in 1878 at Oberon and grew up near Trangi in western New South Wales. Her family, the Harveys, moved to Manly for a period after a younger brother, George, contracted polio (one of the treatments was “sea-bathing”). She met and married a public servant 15 years her senior, Edward Bryant. They had three children but the couple separated not long before Edward died in 1926. Later that year, Bryant began instruction with the Australian Aero Club at Mascot in Sydney. At the time, the site of the current international airport was just a large, grassy expanse with a few buildings and hangars. Bryant was accepted by the Aero Club’s chief instructor, Captain Edward Leggatt (himself a noted first world war fighter pilot), soon after the club had opened its membership to women. Even then, though, she was unusual: here was a 49-year-old mother of three taking up the challenge of flying which, in the 1920’s, was still as dangerous as it was exciting and glamorous. Millicent Bryant (second from left) with other aviators beside her De Havilland Moth. Author provided courtesy of Mary Taguchi. She quickly progressed, ahead of two other younger, women students, and made her first solo flight in February, 1927. By this time, newspapers all around Australia were following her story, and in late March she took the test for the “A” licence that would enable her to independently fly De Havilland Moth biplanes. She passed, and with the issue of her licence by the Ministry of Defence, Bryant was acclaimed as the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia. Millicent Bryant’s training certificate from the Aero Club of Australia (NSW Section). Her ‘A’ Licence was issued by the Department of Defence in April, 1927 Why, then, isn’t she better known in our day? While Bryant immediately began training for a licence to carry passengers and flew regularly in the months that followed, it was her particular misfortune to step onto the Sydney ferry Greycliffe on its regular 4.14pm run to Watson’s Bay on November 3, 1927. Less than an hour later, she was among 40 dead after the ferry was cut in half off Bradley’s Head by the mail steamer Tahiti. It was Sydney’s worst peacetime maritime disaster. Bryant was still only 49. Her funeral two days later was attended by hundreds of people and accorded a remarkable aerial tribute, as the Wellington Times reported: Five aeroplanes from the Mascot aerodrome flew over the procession as it wended its way to the cemetery. As the burial service was read by the Rev. A. R. Ebbs, rector of St. Matthew’s, Manly, one of the planes descended to within about 150 feet of the grave, and there was dropped from it a wreath of red carnations and blue delphiniums … Attached to the floral tribute was a card bearing the following inscription: 5th November, 1927. With the deepest sympathy of the committee and members of the Australian Aero Club — N.S.W. section. A pioneer in life as well as the sky Bryant’s story quickly lapsed into obscurity. Fortunately, some 80 years later, the rediscovery in the family of a collection of letters and other writings has enabled Bryant’s life beyond her flying achievement to be rediscovered. The letters were — and are still until they are added to the collection of Bryant’s papers in the National Library — held by her granddaughter, Millicent Jones of Kendall, NSW, who rediscovered them in storage at her home. The main correspondence is a conversation with her second son, John, in England. It covers the period she was flying, though it only moderately expands on the flights recorded in her logbook. However, her letters and writings reveal much more about Bryant herself, her relationships, her feelings and her leisure, business and political activities. And they make it apparent that she was as much a pioneer in life as well as in the sky. A clipping from The Bulletin, February 24, 1927. The Bulletin., Author provided For one, flying was not Bryant’s only unconventional interest. She was also an entrepreneur, registering an importing company in partnership with John, who went on to become a pioneer of the Australian dairy industry. She opened a men’s clothing business, Chesterfield Men’s Mercery, in Sydney’s CBD. However, disaster struck when it was inundated with water mere weeks after opening, following a fire in the tea rooms upstairs. Bryant then became a small-scale property developer, buying and building on land in Vaucluse and Edgecliffe. She’d been well tutored in this by her father, grazier Edmund Harvey (a grandfather of billionaire Gerry Harvey), whose own holdings eventually included a large part of the Kanimbla Valley west of the Blue Mountains. An excellent horsewoman, Bryant was also an early motorist who had driven over 35,000 miles around NSW and who could fix her own car. She was a keen golfer and reader and even a student of Japanese at the University of Sydney. A key writing fragment by Millicent Bryant (c.1924). Author provided Several fragments of a family saga she planned to write, based on her own life, are among her papers. One sheet, entitled “A Life”, summarises in a series of rough notes rather more than she might have told anyone about her inner world. Marriage – mistakes – children – despondency. Ill-health. Great desire to “live” and create things… She notes that a trip abroad was a complete success but it furnished a heart interest which lasted for fourteen years until hope died owing to a marriage. This fragment provides some background to her taking, in her forties, the unusual step at that time of leaving her marriage and family home to start life afresh with her sons. This was not long before she took her first flight, probably with Edgar Percival, a family friend and later a successful aircraft designer whose planes won air races and were noted for their graceful lines. Vigour, values and conflicts Growing up in the NSW inland late in the 19th century, Bryant would have begun with a fairly traditional view of what it meant to be a wife and mother. However, her early life was also “free-spirited” (as one newspaper described her upbringing) and her determination to make decisions and shape her own life put her on a collision course with gender role expectations common at the time. Learning to fly, especially in middle age, was a breakthrough she pursued perhaps even more keenly after being denied work with the Sydney Sun newspaper solely because she was married. Bryant clearly came to hold strong ideas about what a woman could and couldn’t do, and her life shows a determination to make her own path, despite confronting obstacles that are still familiar in our own time. Bryant is not just a figure in aviation history. Her life — spanning the colonial period, the newly-federated nation and the tragedies of World War I — came to reflect the vigour, values and conflicts of Australia in the early 20th century. In 2006 a new memorial to Millicent Bryant was placed in Manly (now Balgowlah) Cemetery. It was dedicated by the late Nancy Bird Walton, pictured with Gaby Kennard (left) the first Australian woman to fly a single-engine plane around the world, and (right) a great-great-granddaughter of Millicent Bryant, Matilda Millicent Power-Jones. Author provided, Author provided1 point

-

Time has flown by with November 23 marking the 90th anniversary of the first flight from what was the Western Junction Aerodrome and is now the Launceston Airport. The first flight in 1930 was undertaken by pilot Joe Francis in the Gipsy Moth VH-ULM, leased by the Defense Department to the Tasmanian Aero Club. Club historian Lindsay Millar said the first flight was crucial to aviation in the state. "That first flight really marked the beginning of permanent commercial aviation in Tasmania." "From that very beginning, that first flight here at this airport on November 23, 1930, that was the catalyst for everything." The flight led to the formation of Tasmania's first air service, Flinders Island Airways, which eventually, after many different changes and amalgamations, became Australian National Airways, one of the world's largest airlines. Mr Millar said the anniversary crept up on them. "It is amazing and I have been privileged to belong to the Aero Club since 1956. I have been able to share the history of that club in that period," he said. The plane that made the historical first flight is also, once again, touring the skies. The restoration of the plane was started back in 2002 and was completed in 2012 with the original Aero Club colours. The VH-ULM after its restoration was finished in 2012. "The incredible thing about the flight VH-ULM is that the aircraft still exists and is now flying in Queensland," Mr Millar said. "That aircraft after being in private hands for some years and then in a a museum, it's back in the air again, better than brand new." The Tasmanian Aviation Historical Society president Andrew Johnson said it was remarkable the plane was still running. "This aircraft has been restored and looked after and still flying. That makes the whole story really special." Lindsay Millar with model of first flight plane. Mr Johnson said the first flight was the start of quite a significant aviation story in Tasmania. "That first flight led to numerous other flights and to individuals who were pioneers in aviation taking up the concept of flight and developing it from, I suppose a bit of a novelty idea, to commercial flying." "It did pave the way for others." On November 23, the Tasmanian Aero Club rooms will host a special function to recognise the anniversary of the flight and celebrate how far aviation has come because of that moment. "We believe it's an important story and that's why the [TAHS] was formed - to shine some light on it and I think that's the start of it," Mr Johnson said. "From now on we will start to really recognise the events and the significant dates of aviation in Tasmania."1 point

-

Wingsuit flying certainly captured folks' attention when it first hit the mainstream around the turn of the millennium, sparking a wave of GoPro and Red Bull videos. Human flight had never been so personal or so physical as these intrepid maniacs half-fell, half glided through rocky gaps and mountain passes like turbocharged flying squirrels. The name of the game quickly became to see how close you could fly to things without hitting them, in search of the ultimate rush and the biggest view counts. But these devices were limited in that your only source of acceleration was gravity itself, and your flight profile could only ever take you downward. No longer. Stuntman Peter Salzmann had been thinking for years about how to add some sustainable propulsion and climbing ability to the wingsuit experience, and he hooked up with creative consultants at BMW's Designworks studio to create a chest-mounted set of electric impellers and a wingsuit that would work with them. At first, he wanted to mount the props in a backpack arrangement, in longer tubes capable of generating more thrust. But the most advantageous airflow would be in front of him, and he found the initial design too heavy. So a chest mounted system it was, with two 5-inch (13-cm), 25,000 rpm impellers in a relatively compact but still pretty chunky unit that has a bit of a submarine kind of look to it. The wingsuit was designed to incorporate air inlets for the propulsion system. There's an on/off switch, a two-finger throttle and a kind of steering facility, as well as a cutoff switch for emergencies. Otherwise, she's even more of a physical thing to fly than a regular wingsuit; you need plenty of core and limb strength to fight the wind and control your motion in the air. The props put out a relatively modest combined 15 kW (20 hp) for around five minutes, but the results are pretty epic; a regular wingsuit's most horizontal glide ratio drops around a meter for every three meters traveled horizontally, and speed tops out around 100 km/h (62 mph), but when Salzmann hits the electric boost, he can hit speeds over 300 km/h (186 mph), and actually gain altitude to fly upwards instead of constantly dropping. After wind tunnel testing, both in BMW's more auto-focused facilities and in a specialized wingsuiting wind tunnel in Stockholm, and around 30 test jumps, it was time for a public demonstration. The initial plan was to demonstrate the suit's climbing capability by taking it to Busan, Korea, and flying over a group of three skyscrapers, in which the final one was much higher than the first two. COVID-19 put paid to that aspiration, so Salzmann settled for something prettier and closer to home, lining up the Del Brüder peaks in the Hohe Tauern mountain range, part of the Austrian alps. Salzmann and a pair of buddies kitted out with regular wingsuits went up to 10,000 feet (3,050 m) in a chopper, counted down, and jumped. The others are there to act as a reference point, and the three hold formation until Salzmann hits the juice and blasts forward. Where his friends have to split off and fly around the final mountain peak, the electric wingsuit allows him to accelerate up and over it. It's not going to blow Yves Rossy's skirt up; the Swiss "Jetman" has four incredibly powerful jet turbine engines on his extraordinary full carbon jetwing design, which allow him to blast off vertically from the ground with computer-controlled stabilization, and shoot vertically upwards like a rocket as well as swooping and soaring like a 400-km/h (250-mph) eagle. But jet turbines are insanely expensive, and so noisy that they rattle windowpanes from miles away. The average wingsuit pilot's chances of ever flying one are very limited. Salzmann's design, on the other hand, looks much more promising. The electric wingsuit has had the full BMW design touch applied to it; it looks very nicely put together, and, dare we say, much more like a product than a prototype. Nobody's saying anything about these things being for sale yet, either now or into the future, but a small electric propulsion unit is not going to cost jet turbine money, and it's hard to imagine an adrenaline-fueled wingsuit pilot in the world that wouldn't be interested in getting that little bit closer to the Icarus dream of soaring through the sky, rising and gliding at will. Indeed, the main issue may turn out to be whether a company like BMW wants its logo on a product that potentially makes its owners go splat. It's one thing to be making promo videos for world-first innovations like this, and another altogether to release these tools into the hands of extreme sportsfolk where the difference between successful and unsuccessful flights can be so gruesome. Things have come a long way since the first "wing suit" flight – a brief and messily fatal leap off the Eiffel tower by Franz Reichelt in 1912 – but wingsuity types don't seem to be able to get their pulses racing without cutting things really fine. Still, I think we can all rest assured that we'll see more of Salzmann and this device as things develop, and that consumer-grade electric wingsuits will soon be a thing, and that this public debut is a significant moment in personal flight and extreme sports. Enjoy the video below.1 point

-

It costs Martin Hone less to fly and maintain his two aircraft than it does his old farm ute. He is one of the 10,000 Australians who have worked out how to fly for fun, and on the cheap — with a recreational pilot's certificate. With safer aircraft, cheaper training and relaxed rules, flying schools and hobbyists are reporting that more people are taking up flying for recreation. At least those who know about it. Turns out you do not have to be Richard Branson or John Travolta to own your own plane or fly to Crab Claw Island for breakfast. 'Pastime just about anybody can afford' The recreational certificate allows people to fly smaller, simpler aircraft, like this two-seater kit ultralight from Florida.(Supplied: Australian Aviation Archives) Mr Hone grew up riding his bike to Moorabin Airport to watch the planes take off. Worried his eyesight was not good enough or he would never be able to afford it, he put his flying dream behind him. That was until he found Recreational Aviation Australia. Formerly the Australian Ultralight Federation, RAAus provided a window for Australians looking to fly small aircraft for fun in 1983. "It wasn't for the average person effectively to go flying for fun," Mr Hone said. We exploded in popularity An Australian Lightwing GR582 sits at the Top End Flying Club in Darwin.(Supplied: Lloyd Greenfield) Under the recreational pilot's certificate, pilots can fly with one other person in a recreation registered aircraft weighing under 600kg at take-off. They cannot fly at night or charge for their flying services (unless instructing). RAAus CEO Michael Linke said it was not until 2007 when light-sport aircraft — heavier and more sophisticated than their ultralight predecessors — came on the market that Australians took to the air in droves. When it comes to medical requirements, RAAus CEO Michael Linke said the same Austroads private driver's licence health standard applied for recreational pilots. So if you are fit to drive a car, you are fit to operate a RAAus aircraft. You can assemble your own kit plane You can pay anywhere from $5,000 for a two-stroke motor aircraft to well over $200,000 at the upper end.(Supplied: Lloyd Greenfield) It took Josh Mesilane 32 hours and $5,760 to get his certificate. The 34-year-old had just bought a house, started a business and was looking to start a family when he realised his flying dreams in 2018. Before that he had no idea recreational aviation existed. The certificate requires a minimum of 20 hours, five of which are solo hours. With schools typically charging between $200 and $300 an hour, you are looking at a bare minimum of $4,000 for your certificate. A Cross Country endorsement will take an extra 12 hours and allows you to fly anywhere in uncontrolled air space (about 95 per cent of Australia). Ross Kilner flies with his dog Bongo from Robe in South Australia's Limestone Coast.(ABC South East SA: Bec Whetham) Comparatively, a general aviation licence issued by CASA costs a minimum of $16,000 and 40 hours of flight time. When it comes to owning an aircraft you can pay anywhere from $5,000 for your "rag and tube", two-stroke motor aircraft to well over $200,000 on your top end. If you're really good with the tools, you can assemble your own kit plane. The return of old-school bush flying Recreational Aviation Australia offers a maintenance course that allows pilots to maintain their own aircraft. Another way to save money... if you are good with the tools that is!(Supplied: Lloyd Greenfield) Former Air Force pilot Dan Compton has made a business teaching recreational pilots at his airfield in Dubbo, 388 kilometres north-west of Sydney. Despite advancements in aviation and aircraft, he has been inundated with people wanting to experience flying "the way it was". Part of the "survival flying" Mr Compton teaches at Wings Out West is the ability to land anywhere. "Everything other than an airport looks big (and) scary." — Dan Compton(Supplied: Dan Compton) He said it was all too common for people to learn to only fly and land on airports, which is problematic. "Then everything other than an airport looks big (and) scary," Mr Compton said. Oh, the places you'll go! Dan Compton says most of his students are in their 20s and 30s.(Supplied: Dan Compton) Being able to land anywhere gives pilots the confidence to fly anywhere. The Top End Flying Club does a really good job of that. Club member Fiona Shanahan has enjoyed learning to fly in Darwin since moving from Melbourne. "You (can) go out to the Adelaide River floodplains and see buffalo and pigs and kangaroos and birds, all sorts of things," Ms Shanahan said. "Occasionally you can see some crocodiles sitting in rivers… you don't get to see that from the ground." A recreational aircraft flies over the Northern Territory at sunset.(Supplied: Lloyd Greenfield) Weekend fly-ins are a regular occurrence at the club. "It's not uncommon for a group of us to go and fly to Crab Claw Island for breakfast," Ms Parker said. Peter Brookman bought the Keith airfield from council a few years ago. He has two planes in the hangar there.(ABC South East SA: Bec Whetham) Mr Linke said pilots could land just about anywhere — with a few requirements, such as a windsock and indicators. Is it safe? Two young aviators at the Top End Flying Club in Darwin.(Supplied: Lloyd Greenfield) Mr Linke said recreational aircraft were just as safe as CASA aircraft. "They're obviously not as safe and don't have the same controls as Qantas and planes like that — they're carrying 500 people." Amateur-built aircraft must meet similar standards. "They've got to be inspected, they've got to get a second person inspecting when you're putting an aircraft together, you've got to get checks and balances together when you're building the aircraft," Mr Linke said. 'It'd be nice to see women' Mr Compton said most of his students are in their 20s and 30s. Then there are the teenagers looking to get a head start. Fiona Shanahan had no idea she would become an avid pilot when she moved from Melbourne to Darwin for work.(Supplied: Fiona Shanahan) "The most lacking thing here in my school… is female pilots and I think that's generally everywhere. 'We use it to bribe them' Tony Wulff and his wife, Peta, added car seats to the back for their two young kids.(Supplied: Tony Wulff) Tony Wulff, in central Victoria, flies the family's plane Percy from their farm strip at Heathcote. He and his wife, Peta, added two car seats in the back to accommodate their two favourite passengers "They really love it. They sit in the back in their car seats and have their little headsets on and hang out the window," Mr Wulff said. "We use it to bribe them quite regularly.1 point