-

Posts

9,288 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

108

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Downloads

Blogs

Events

Store

Aircraft

Resources

Tutorials

Articles

Classifieds

Movies

Books

Community Map

Quizzes

Videos Directory

Everything posted by Admin

-

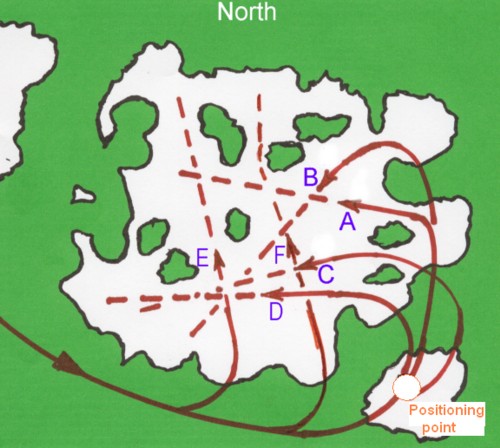

On June 30, 1943, Flight Sergeant Colin Duncan and his squadron of Spitfires took off on a mission to intercept Japanese aircraft over Darwin. But while the ensuing battle has for decades been marked in folklore, the whereabouts of Duncan's shot-down plane has, until now, remained a mystery. The Spitfire A58-2 Duncan was flying caught fire, engulfing the cabin in flames and sending the aircraft plummeting towards the ground in a spiral dive. Desperate to escape, the rip cord to release his aircraft canopy failed, leaving Duncan scrambling to force it off and struggle out of the aircraft to parachute to the ground. Flight Sergeant Colin Duncan defied death to make it back to Darwin.(Supplied: Australian War Memorial) But his battle was only just beginning. Duncan was stranded with severe burns in tough Top End terrain, alone and with minimal supplies, and it would be another five days before he was rescued. Bombing of Darwin: 70 years on On February 19, 1942, Japanese forces launched air raids on Darwin. Hundreds were killed in the attack. This compilation of videos, pictures and recollections take a look a of the most significant moments in Australian history. Seventy-six years since that fateful flight, Colin Duncan's grandson has visited the wreckage of his grandfather's plane for the first time. As he walked through the untouched debris of the Spitfire's final resting place, Duncan Williams was left shocked. "It's a genuine time capsule," he said. "I didn't expect it. I don't know what I was expecting really. Mr Williams said he was amazed his grandfather managed to escape alive. On viewing the wreckage, he remarked on how the Spitfire hit the ground with such force it left only a mangled mess of metal. "He was very lucky to get out alive," Mr Williams said. "Here we've got the cannons. You can see the angle the plane hit the ground. The aircraft wreck is now protected under the Northern Territory Heritage Act.(ABC News: Ian Redfearn) The remote location in Litchfield National Park, about 110 kilometres south of Darwin, means the Spitfire has remained undiscovered until recently. And with the crash site immensely difficult to reach and only accessible by helicopter, the plan is to preserve the wreckage at its final resting place. 'This is our Pearl Harbour' The RAAF has handed ownership of the wreckage to the Northern Territory Government in the hope it will help tell the story of Darwin's role in World War II. According to RAAF Air Commodore John Meier, the new find in the Top End outback is testament to the Darwin's often forgotten place in modern wartime history. Hundreds were killed in air battles over Darwin during World War II.(ABC News: Ian Redfearn) "We only had a few Spitfires in Australia, and this one is of major significance because it was lost in the battle of Darwin," he said. "If you compare it to Pearl Harbour, that everyone knows about, this is our Pearl Harbour, and it's not particularly well known by the Australian population." Colin Duncan continued flying Spitfires in the war, and later played cricket for Victoria as well as running a successful building company. He died in 1992 from cancer, leaving behind his wife and two daughters.

-

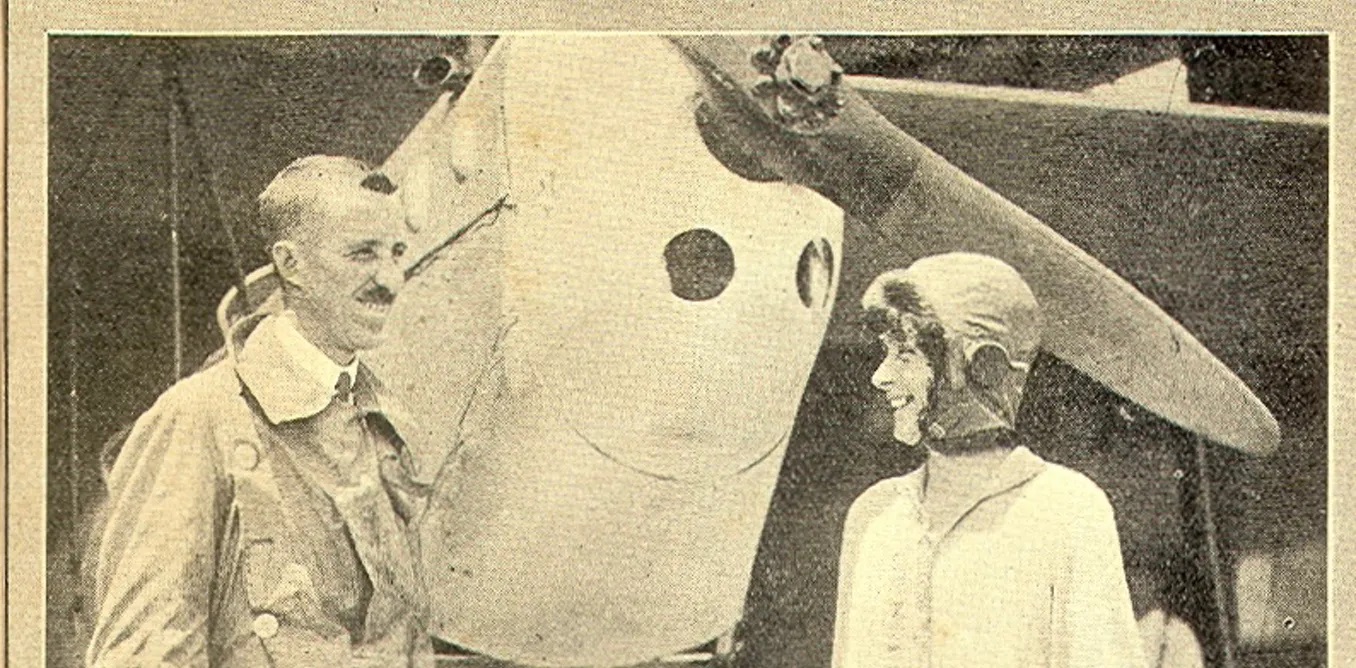

Before the glamorous flyers of the 1930s like Amelia Earhart, “Chubby” Miller and Nancy Bird Walton, another woman opened the way to the skies — and were it not for a tragic twist of fate, her name might now be just as familiar. Her name was Millicent Maude Bryant, and in early 1927, she became the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia. She was also first in the Commonwealth outside Britain. Millicent Bryant c.1919. Portrait by Monte Luke. Author provided A boundary-pusher who met an untimely end Millicent was born in 1878 at Oberon and grew up near Trangi in western New South Wales. Her family, the Harveys, moved to Manly for a period after a younger brother, George, contracted polio (one of the treatments was “sea-bathing”). She met and married a public servant 15 years her senior, Edward Bryant. They had three children but the couple separated not long before Edward died in 1926. Later that year, Bryant began instruction with the Australian Aero Club at Mascot in Sydney. At the time, the site of the current international airport was just a large, grassy expanse with a few buildings and hangars. Bryant was accepted by the Aero Club’s chief instructor, Captain Edward Leggatt (himself a noted first world war fighter pilot), soon after the club had opened its membership to women. Even then, though, she was unusual: here was a 49-year-old mother of three taking up the challenge of flying which, in the 1920’s, was still as dangerous as it was exciting and glamorous. Millicent Bryant (second from left) with other aviators beside her De Havilland Moth. Author provided courtesy of Mary Taguchi. She quickly progressed, ahead of two other younger, women students, and made her first solo flight in February, 1927. By this time, newspapers all around Australia were following her story, and in late March she took the test for the “A” licence that would enable her to independently fly De Havilland Moth biplanes. She passed, and with the issue of her licence by the Ministry of Defence, Bryant was acclaimed as the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia. Millicent Bryant’s training certificate from the Aero Club of Australia (NSW Section). Her ‘A’ Licence was issued by the Department of Defence in April, 1927 Why, then, isn’t she better known in our day? While Bryant immediately began training for a licence to carry passengers and flew regularly in the months that followed, it was her particular misfortune to step onto the Sydney ferry Greycliffe on its regular 4.14pm run to Watson’s Bay on November 3, 1927. Less than an hour later, she was among 40 dead after the ferry was cut in half off Bradley’s Head by the mail steamer Tahiti. It was Sydney’s worst peacetime maritime disaster. Bryant was still only 49. Her funeral two days later was attended by hundreds of people and accorded a remarkable aerial tribute, as the Wellington Times reported: Five aeroplanes from the Mascot aerodrome flew over the procession as it wended its way to the cemetery. As the burial service was read by the Rev. A. R. Ebbs, rector of St. Matthew’s, Manly, one of the planes descended to within about 150 feet of the grave, and there was dropped from it a wreath of red carnations and blue delphiniums … Attached to the floral tribute was a card bearing the following inscription: 5th November, 1927. With the deepest sympathy of the committee and members of the Australian Aero Club — N.S.W. section. A pioneer in life as well as the sky Bryant’s story quickly lapsed into obscurity. Fortunately, some 80 years later, the rediscovery in the family of a collection of letters and other writings has enabled Bryant’s life beyond her flying achievement to be rediscovered. The letters were — and are still until they are added to the collection of Bryant’s papers in the National Library — held by her granddaughter, Millicent Jones of Kendall, NSW, who rediscovered them in storage at her home. The main correspondence is a conversation with her second son, John, in England. It covers the period she was flying, though it only moderately expands on the flights recorded in her logbook. However, her letters and writings reveal much more about Bryant herself, her relationships, her feelings and her leisure, business and political activities. And they make it apparent that she was as much a pioneer in life as well as in the sky. A clipping from The Bulletin, February 24, 1927. The Bulletin., Author provided For one, flying was not Bryant’s only unconventional interest. She was also an entrepreneur, registering an importing company in partnership with John, who went on to become a pioneer of the Australian dairy industry. She opened a men’s clothing business, Chesterfield Men’s Mercery, in Sydney’s CBD. However, disaster struck when it was inundated with water mere weeks after opening, following a fire in the tea rooms upstairs. Bryant then became a small-scale property developer, buying and building on land in Vaucluse and Edgecliffe. She’d been well tutored in this by her father, grazier Edmund Harvey (a grandfather of billionaire Gerry Harvey), whose own holdings eventually included a large part of the Kanimbla Valley west of the Blue Mountains. An excellent horsewoman, Bryant was also an early motorist who had driven over 35,000 miles around NSW and who could fix her own car. She was a keen golfer and reader and even a student of Japanese at the University of Sydney. A key writing fragment by Millicent Bryant (c.1924). Author provided Several fragments of a family saga she planned to write, based on her own life, are among her papers. One sheet, entitled “A Life”, summarises in a series of rough notes rather more than she might have told anyone about her inner world. Marriage – mistakes – children – despondency. Ill-health. Great desire to “live” and create things… She notes that a trip abroad was a complete success but it furnished a heart interest which lasted for fourteen years until hope died owing to a marriage. This fragment provides some background to her taking, in her forties, the unusual step at that time of leaving her marriage and family home to start life afresh with her sons. This was not long before she took her first flight, probably with Edgar Percival, a family friend and later a successful aircraft designer whose planes won air races and were noted for their graceful lines. Vigour, values and conflicts Growing up in the NSW inland late in the 19th century, Bryant would have begun with a fairly traditional view of what it meant to be a wife and mother. However, her early life was also “free-spirited” (as one newspaper described her upbringing) and her determination to make decisions and shape her own life put her on a collision course with gender role expectations common at the time. Learning to fly, especially in middle age, was a breakthrough she pursued perhaps even more keenly after being denied work with the Sydney Sun newspaper solely because she was married. Bryant clearly came to hold strong ideas about what a woman could and couldn’t do, and her life shows a determination to make her own path, despite confronting obstacles that are still familiar in our own time. Bryant is not just a figure in aviation history. Her life — spanning the colonial period, the newly-federated nation and the tragedies of World War I — came to reflect the vigour, values and conflicts of Australia in the early 20th century. In 2006 a new memorial to Millicent Bryant was placed in Manly (now Balgowlah) Cemetery. It was dedicated by the late Nancy Bird Walton, pictured with Gaby Kennard (left) the first Australian woman to fly a single-engine plane around the world, and (right) a great-great-granddaughter of Millicent Bryant, Matilda Millicent Power-Jones. Author provided, Author provided

-

Personally I would feel much safer coming down in a jab than many of the other aircraft around. Glad to hear the pilot is relatively ok and I wish him well like I am sure most of you do as well

-

Queensland motorists could get a rare glimpse of two vintage Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) planes as they are escorted by police convoy on a 1,600-kilometre road trip across Queensland. The Mirage fighter jet A3-55 and Winjeel Trainer A85-403 started their journey just after midnight Friday from the Amberley RAAF base. The restored aircraft were expected to arrive in Townsville on Sunday to go on permanent display at the RAAF's Aviation Heritage Centre, ahead of next year's Air Force Centenary. The convoy will be stopping about every two hours with overnight stays in Banana and Moranbah. Other towns that are expected to see the aircraft include Toowoomba, Dalby, Chinchilla, Miles, Wandoan, Taroom, Theodore, Dululu, Dingo and Charters Towers. Planes restored 'to former glory' The Mirage, or French Lady, was a single-seat frontline fighter that flew between 1967 and 1987, capable of a speed of more than 2,000 kilometres an hour and was armed with guns, missiles and bombs. The Winjeel — an Aboriginal word for 'young eagle' — was a basic flight trainer that flew between 1958 and 1975. They have been restored by members of the Amberley RAAF Base's Air Force History and Heritage Branch. Warrant Officer Mike Downes has joined the convoy and said it was a unique spectacle of aviation history. An historic photo of the Mirage fighter jets in flight.(Supplied: Department of Defence) "I'm a bit of an aviation nut, I love my aircraft," WOFF Downes said. "The interest level has been generated in places like Claremont and Moranbah and Banana. "People say I used to work on that or my father flew them." Part of the restoration included clearing out the cockpit and a new lick of paint. "We've painted the aircraft in the colours of number 76 Squadron so it represents the colours that that aircraft operated in back when it was flying," WOFF Downs said. Winjeel Trainer A85-403 left Amberley on Friday and is expected to arrive in Townsville on Sunday.(Department of Defence) 'It will take up most of the road' WOFF Downes said it has taken about a year to organise the logistics, including police escorting the Mirage. "We've taken the wings off the Winjeel so it's quite a narrow load," he said. The wings of the Winjeel have been removed.(Supplied: RAAF) "The Mirage is a different story completely, it's actually 8.2 metres wide from wingtip to wingtip so it will take up most of the road." He said flying the aircraft to Townsville would have required a rebuild. "It would be a mammoth task to make it air-worthy," he said. "This aircraft has been turned into a static display aircraft so we've removed the engine and a lot of the other equipment." The Mirage will be escorted by a police convey for the entire journey. The two aircraft will meet up in Charters Towers before heading to their final destination.

-

Australian company AMSL Aero has unveiled what it claims to be the world’s first electric air ambulances, launching the first prototype aircraft in Sydney on Wednesday as part of a partnership with air-rescue organisation CareFlight. The Vertiia prototype has been designed to take-off vertically, like a helicopter, but once airborne, flies with the aid of fixed wings, in the same way as a plane does. AMSL Aero says that this combination provides the aircraft with significant flexibility in where it can land, while also providing greater speed and energy efficiency. The company says that the aircraft would reach a cruising speed of up to 300 km/h and a range of up to 250km as an all-electric model with batteries, and a hydrogen fuelled version achieving a range of up to 800km. The aircraft was launched by deputy prime minister and transport minister Michael McCormack, who welcomed the prospect of an all-electric aircraft that had the ability to access difficult areas. “I remember growing up and watching the Jetsons and marveling at that futuristic technology. It’s right here, right now and it’s happening,” McCormack said. “What an exciting day to think that we’ve got a what will be a carbon neutral plane taking off, landing, in sites where there’s a mass casualty or indeed a hospital where somebody’s young, or somebody not so young, needs urgent medical retrieval and in sometimes even country areas, you can’t get to places easily” AMSL Aero CEO Andrew Moore says the vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) allows the aircraft to access areas without the need of a runway, and it had entered into a partnership with CareFlight for the development of an “electric aero ambulance”, that could provide crucial medical support to regional communities. Deputy prime minister Michael McCormack, with AMSL Aero co-founders Andrew Moore and Siobhan Lyndon. “Vertiia will instantly enable greater access to medical services for vulnerable remote, rural, and regional communities, offering new models of care through rapid and low-cost connectivity,” Moore said. “Unlike aeromedical planes that require a runway, Vertiia will carry patients directly from any location straight to the hospital, significantly reducing the complexity and time transporting vulnerable patients. “It will also be quieter and safer than helicopters, and will eventually cost as little as a car to maintain and run, transforming aeromedical transport into a far more affordable, accessible, safer, and reliable option.” CareFlight’s medical director Dr Toby Fogg said that the organisation had been attracted to the Vertiia aircraft, as its efficiency and lower operational costs, while providing the same flexibility as a helicopter, meant that it could potentially deploy more aircraft for the same cost, reaching more people needing assistance. “Initial scoping and modelling suggest that with Vertiia we would be able to reach more Australians. For example, the price point of operating Vertiia versus helicopters and fixed wing aircraft would mean we can purchase a much larger fleet aircraft, by several multiples. The lower operational costs would allow us to hire more doctors, nurses and paramedics,” Fogg said. AMSL Zero was founded in Australia in 2017 by co-founders Andrew Moore and Siobhan Lyndon with the initial versions of the aircraft having the ability to carry a pilot, a medic as well as transporting a patient. The partnership between AMSL Aero and CareFlight is being supported as part of a $3 million Cooperative Research Centres Project grant, and would include the University of Sydney and autonomy and sensing specialists, Mission Systems as part of the collaboration. CareFlight pilots will be involved in the design of the Vertiia aircraft, ensuring it meets the needs of medical services and could see electric air ambulances deployed within the next few years. The company already has its eyes set on the creation of a commercial version of the aircraft having the capacity to transport up to four people. Both the all-electric and hydrogen fuelled versions of the aircraft have the potential to operate with zero associated greenhouse gas emissions. A prototype of the Vertiia aircraft was unveiled at AMSL’s aerodrome located at Bankstown Airport in Sydney, where the aircraft has been undergoing construction. The aircraft is expected to undertake test flights from a facility at Narromine Airport, just outside of Dubbo. The Vertiia aircraft is being touted as one of the world’s most energy efficient aircraft and has the potential to be deployed in a range of applications, including commercial transport and flying taxis.

-

Bundaberg’s Jabiru Aircraft has created face shields with the help of 3D printing to provide extra protection for frontline workers dealing with Covid-19 cases. Bundaberg’s Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd, whose business usually focuses on producing light sport aircraft and engines, has responded to the current pandemic crisis by creating face shields utilising 3D printing technology to provide extra protection to frontline health workers dealing with Covid-19 cases. With these efforts Jabiru Aircraft joins other manufacturing entities and individuals around the world in producing emergency Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during a time of global shortage. Jabiru Aircraft Business Manager Sue Woods said last Friday she and an employee, engineer Alex Swan, were looking at ways to support health care workers during the current public health situation, and with a little ingenuity and the help of a 3D printer they were able to design and commence the manufacture of the PPE. Sue said they were very concerned for the wellbeing of paramedics, GPs and medical personnel who were most at risk of contracting the virus. They hoped the extra layer of protection offered by the face shield would keep these essential people healthy. Both Sue and Alex have family members who work in healthcare, and they were on the same path of thinking – wanting to ensure not only their loved ones stayed safe, but also others facing the Coronavirus firsthand. 3D printers used to create face shields “I came to work one day after watching footage on the shortage of PPE and thought ‘what can we do'?” Sue said. “Alex experimented with cutting the visor section until we had the right shape and he modified the headband 3D file to accommodate glasses underneath. “We then had both a local dentist and a local doctor try the face shields, and check with sterilising products, and we had good response.” Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd has designed and manufactured emergency Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during a time of global shortage in result of the Covid-19 situation. Two 3D printers are used by Jabiru Aircraft to create the head band for the face shield and the transparent polycarbonate for the visor is cut to shape with a flatbed CNC router. “Our engineer Alex Swan has been very motivated with this project and volunteered much of his own time, getting up in the middle of the night to keep the 3D printers going 24/7,” Sue said. “We have two 3D printers and Alex took them home so he could get up at 2am to press the button to start the next headband.” Sue said it took less than a week to develop the idea and start production of the face shields, and they hope to have 100 finished and shipped to paramedics in Western Australia by Monday. She said the slowest part of the production was the 3D printing and she was thankful for the support from other local organisations who offered assistance. “To increase our production rate of the 3D printed component, CQUniversity Bundaberg and Gladstone and Makerspace Bundaberg and Hervey Bay, along with CQUniversity Makerspace have jumped on board very quickly, and we now have several additional 3D printers in action,” she said. “We are also getting offers of assistance from schools in the local community.”

-

Time has flown by with November 23 marking the 90th anniversary of the first flight from what was the Western Junction Aerodrome and is now the Launceston Airport. The first flight in 1930 was undertaken by pilot Joe Francis in the Gipsy Moth VH-ULM, leased by the Defense Department to the Tasmanian Aero Club. Club historian Lindsay Millar said the first flight was crucial to aviation in the state. "That first flight really marked the beginning of permanent commercial aviation in Tasmania." "From that very beginning, that first flight here at this airport on November 23, 1930, that was the catalyst for everything." The flight led to the formation of Tasmania's first air service, Flinders Island Airways, which eventually, after many different changes and amalgamations, became Australian National Airways, one of the world's largest airlines. Mr Millar said the anniversary crept up on them. "It is amazing and I have been privileged to belong to the Aero Club since 1956. I have been able to share the history of that club in that period," he said. The plane that made the historical first flight is also, once again, touring the skies. The restoration of the plane was started back in 2002 and was completed in 2012 with the original Aero Club colours. The VH-ULM after its restoration was finished in 2012. "The incredible thing about the flight VH-ULM is that the aircraft still exists and is now flying in Queensland," Mr Millar said. "That aircraft after being in private hands for some years and then in a a museum, it's back in the air again, better than brand new." The Tasmanian Aviation Historical Society president Andrew Johnson said it was remarkable the plane was still running. "This aircraft has been restored and looked after and still flying. That makes the whole story really special." Lindsay Millar with model of first flight plane. Mr Johnson said the first flight was the start of quite a significant aviation story in Tasmania. "That first flight led to numerous other flights and to individuals who were pioneers in aviation taking up the concept of flight and developing it from, I suppose a bit of a novelty idea, to commercial flying." "It did pave the way for others." On November 23, the Tasmanian Aero Club rooms will host a special function to recognise the anniversary of the flight and celebrate how far aviation has come because of that moment. "We believe it's an important story and that's why the [TAHS] was formed - to shine some light on it and I think that's the start of it," Mr Johnson said. "From now on we will start to really recognise the events and the significant dates of aviation in Tasmania."

-

Packing for travelling light Always a problem – so many compromises have to be made. The old adage, "If in doubt, leave it out ...", needs to be applied often, but there's still lots of pondering, hefting, agonizing, and re-packing. I've gone through the process dozens of times over the years, preparing for long backpacking and motorbike trips, and now ultralights. It does get easier, especially with the lightweight gear now on the market, and I have learned a few tricks that I'll pass on to anyone interested. As you'll see, I like my comforts as well, and have found ways to bring them with me, folding chair included! First of all, I would never leave my self-inflating mattress behind. It's 3/4 length, 25 mm thick when inflated, rolls up to a small bundle deflated, and weighs very little. You'd think that thickness (thinness) wouldn't be of much use, but it does wonders for a comfortable sleep! If the cost seems too much (about $90 when I got mine), then at least get one of those blue foam mats. Even 8 mm thickness of that blue foam is enough to make a really big difference on cold, hard ground, and cut down to 3/4 length also weighs very little. To carry the mattress on the aircraft, I use a couple of short pieces of light bungee cord (3–4 mm diameter) tied in loops like strong rubber bands to keep the mattress rolled-up, then another couple of loops of the bungee tied around a convenient tube on the aircraft, and just slip the rolled mattress under these loops — nothing to tie/untie every time, and very secure. Inside the wing would be a good place, if you have access on your aircraft. A sleeping bag is the next obvious necessity for camping out. There are lots of options here, but I find that combining a light-weight sleeping bag with lots of cold weather flying clothing gives the most flexible combinations for all-weather flying and camping at minimum weight. So let's first have a look at flying clothing. Flying warm Having been raised on the central plains of Canada, then spending months at a time living on motorcycles in all weathers has taught me a bit about dressing to survive the cold. I did a lot of suffering in those early days before I learned better. Let's start at the inside, where you can make the biggest gains in warmth. I really don't understand why long underwear gets the jokes and ridicule that it does. It's by far the most effective warm clothing of all, for it's weight. The polypropylene thermal underwear available these days is soft, form-fitting and stretchy, and easily fits under other clothing. It wicks moisture away from the skin and provides a layer of warm air next to the skin, just like I would imagine the layer of fur does for a cat! When not being worn it packs into a soft bundle and weighs very little. The jeans and shirt going over it provide very little warmth for all their weight; far warmer and more comfortable is to travel in a track suit. Over the shirt go a couple of lamb's wool sweaters. These are the soft, fluffy, 'lounging' sweaters, either V-neck, or crew neck to your preference. Two (or more) layers like this is much, much, warmer and lighter than one heavy jumper, and more flexible and comfortable. When not needed they stuff easily into your travelling bag. When your flying jacket goes over all this fluffy bulk you'll feel like a fat teddy bear, but at least you'll be a warm and cosy bear! The sweaters are for sale in 'recycled clothing stores for a couple of dollars each, so not a cost problem, but get a larger size for comfort. (I actually bought a couple of them in Narromine one time, when ferrying an open ultralight from Geelong, and a freezing cold front caught me unprepared; nice and warm all the way after that.) If you wear a flying suit then your legs are already covered, but if you wear a flying jacket, then you need some outer pants – it's no use being a cosy bear on the top while losing all your body heat from your legs. Those insulatedski pants are ideal. They're wind-proof, warm, light-weight, and come well up under the jacket for a good seal. But this isn't all that you can do; don't forget those cold feet. I carry several pairs of light wool socks, and wear two or three pairs at once on a long, cold flight, with another couple of dry pairs to change into at fuel stops. Another important bit of clothing is a scarf, to seal around the collar of your jacket, and protect the back of your neck. I just use a T-shirt for the purpose, since it can double as a spare shirt as well. Even more effective is a balaclava, which will seal in the whole head and neck. For the hands, ski gloves with the tips of the fingers cut off, work well for me – warm and still have good dexterity. Dress like this and you won't be cold, regardless of the conditions. I know that all this seems like a lot of stuff, but the extra, besides what you would wear anyhow, doesn't weigh much at all, and much of it will double for your sleeping gear as well. Of course, the other advantage of all these layers is that you can arrange them to suit the conditions at the time, whereas if you depend only on a very warm flight suit, it can be stifling on a hot day, and yet too bulky and difficult to pack away. Sleeping Sleeping warm So I just carry a lightweight summer sleeping bag all year. But a roomy one, because inside it I wear as much of the flying clothing as is necessary for the temperature of the night. I don't know where the myth comes from about it being warmer in a sleeping bag with your day clothes off — I find just the opposite, and I've had many teeth-chattering nights to put it to the test. There are several advantages to wearing lots of clothing inside a sleeping bag; not the least of which is, if you need to get up in the middle of the night for whatever reason, it's no sense exposing any more skin than necessary to that chill night air! As a minimum I use my thermal underwear as pyjamas, and if the night is cold enough, then my track suit pants and a jumper as well. The track suit pants are the ones with two layers of light fabric rather than the thick fleecy ones — lighter and easier to pack away. Then when I get up in the morning to stir up the fire, I'm already dressed enough to be comfortable, without having to get into cold clothes. If it's a really freezing cold night then I'll wear everything (except jeans, they're just too uncomfortable), including flying jacket and ski pants, not forgetting a couple of pairs of dry wool socks and the T-shirt wrapped around my head. With all these options I can be comfortable anywhere from the tropics to the frosty high plains. The sleeping bag should have a hood to keep your head warm, since 20% of body heat is lost there. And it must not have a fleece lining — the fleece feels nice on bare skin but it drags on your clothing when you roll over, and collects every bindi [burr] in the west if it gets a chance. Sleeping really light The next essential for lightweight camping is a 'space blanket' (that may be a trademark name, but I'll use it anyhow). It's also an essential part of any survival kit so I have a space blanket permanently in my aircraft, even for local flights; once again it weighs little and is held in by a couple of loops of light bungee cord around a convenient tube. When camping really light, I use the space blanket as a ground sheet, pulled partly over the sleeping bag on the side which any draught is coming from. Stopping that draught from getting at your back makes a really big difference to staying warm at night. Putting another space blanket right over the sleeping bag sure is nice and warm, but condensation will wet parts of the sleeping bag — but if it's raining it's still a lot better than cold rain soaking the bag. If the second space blanket is set up like a lean-to, with a fire in front, it's like a reflector oven and is the warmest camp of all! Avoid the cheap imitation space blankets on the market, made of that blue tarpaulin material aluminized on one side — they're much heavier and stiffer than the original brand 'Space Blanket', and not nearly as useful. One last essential for sleeping out is a mosquito net! It only takes one persistent mossie at 3 a.m. to ruin a good sleep (and if there's one buzzing around you, others will hear the buzz and come over to get their share). The lightest solution that I've found is to carry one of those fly nets that fits over a hat. So I sleep under my hat and try to tuck the net into the bag — it's awkward and prone to coming loose if I roll around to much, but sure is better than trying to breathe inside the sleeping bag on a tropical night! Five star accommodation Of course the way to really beat the mossies, and get a whole lot of other comforts as well, is to have a tent. And that's possible these days with the light-weight tents on the market. Mine weighs just 2 kg, and is a great little 'cocoon'. It not only keeps the mossies well away, but it stops that chilling draught, keeps the dew off, and provides shelter to keep my gear and boots dry if there's rain in the night. I used to 'sleep rough' with only a ground sheet and sleeping bag, but now I'm hooked on the comforts of my little tent. So what doall those 'very littles'add up to? The flying clothing — ski pants, track suit pants, 2 sweaters, T-shirt, gloves, 5 pairs socks, and thermal underwear — weigh 3 kg. (The flying jacket is so much a part of me that I consider it as part of my personal weight.) The sleeping bag, mattress, and 2 space blankets add another 3 kg, and the optional tent is 2 kg. Stuff it all into a light-weight sports bag (along with a small pillow for real comfort) and that's9 kg — not too bad for a kit that's sufficient for flying and sleeping-out in just about any weather, and in reasonable comfort. Basic survival gear Every aircraft should always carry some basic survival gear, even on short local flights. That may seem a bit extreme to most casual fliers, but let's have a think about it, and maybe you'll decide to carry at least the basics in future. Hopefully it'll never be needed for a critical 'survival' situation, but much more likely just an unplanned night spent out somewhere, due to bad weather or mechanical failure. Water In this hot, dry Australian land it's really amazing to see fliers ignoring all lessons of common sense by flying off without any water at all on board! Even without the possibility of being stranded by an emergency landing, it's really nice to have some good drinking water at hand. I always have at least two litres of water in my aircraft — one litre bottle right handy for a refreshing drink whenever it suits, and another litre bottle secured in the pod. That's enough, if used sparingly, to make a really big difference if I get stranded somewhere overnight. Two litres is the absolute minimum, but if you're going away from the settled coast and the weather is really hot then of course much more is required. To carry more water the best containers these days are those tough nylon water 'bags' sold by good camping stores — much easier to pack into corners of the pod, or wherever, and easier to tie down than hard containers. They're also handy for trimming the balance of an aircraft (seems ridiculous to see some aircraft with a lump of lead permanently in the tail, when a few litres of water would have the same effect, and be a handy reserve as well!) Space Blanket This is the most useful survival equipment you can carry; it could save your life in either hot or cold conditions. I have one permanently secured in my aircraft. It weighs less than very little and is easy to roll up and tie to some tubing somewhere out of the way. One of the most likely causes of being forced down is due to bad weather, and that might well mean being caught out in cold rain for a couple of days or more. No shortage of water, but without shelter it could easily get to hypothermia. In extreme cold, wet conditions it's best to crouch down, or sit in the aircraft seat, with your knees against your chest, trying to be as small as possible, with the space blanket over your head and around you like a shawl. This way you best contain your body heat and shed the cold rain. It gets pretty cramped and uncomfortable, but you can at least survive in some really cold conditions this way. If you have the means of lighting a fire and keeping it going, then the the space blanket rigged as a lean-to can turn a survival situation into real comfort. In the event of being stranded in hot weather, the space blanket once again is a saviour. If you have limited water, then it's very important to reduce the losses. Watch kangaroos for a good lesson on how to manage these conditions. During the heat of the day, especially in drought conditions, they select the best shade they can find and then just lie there without moving at all — same should go with us. Chasing around looking for bush tucker or digging for water is usually a complete waste of precious energy. Tie the space blanket over some low bushes, crawl underneath with the water you have, and lie absolutely still. Try to 'slow down' and get into a state of slumber, breathing as slowly as possible through the nostrils, and stay that way; you can survive much, much longer in this state of suspended animation than if you were up and moving around. Let's hope it never comes to this extreme for any of us, and it shouldn't if you carry an ELT, but it's good to know, just in case ... Fire lighters I always keep at least two of those gas cigarette lighters on hand, one inside the rolled up space blanket, with another one always in the shoulder pocket of my flying jacket. Some purists insist on matches, but my experience indicates that the lighters are much better than even the best 'waterproof' matches — with those lighters that have an adjustable flame it's like lighting a fire with a blow-torch! In Australia it's nearly always possible to find enough suitable wood to light a fire, and that fire can be really essential for survival. With the space blanket rigged as a lean-to in front of a good fire, you can be dry and cosy. Light the fire against a log, with a couple of heavy bits stacked across on top, and it reflects the heat into the lean-to as well as protecting the fire from the rain. VERY IMPORTANT! A campfire isn't all that visible from the air unless it has a good plume of smoke in daylight or a flare-up at night. So if you're depending upon an aerial search (due to your ELT signal of course), then keeping a good fire going is essential. Have a bundle of foliage ready to throw on to make lots of smoke in the daytime, or a big bundle of light branches on hand to make the fire flare up quickly at night, in case you should hear an aircraft approaching. Mirror Another way to assist a search aircraft, or even possibly attract the attention of any passing aircraft, is with a signalling mirror. A bright, persistent flash from the ground really catches the attention, and that's easy to do if you have a mirror on a sunny day, and know how to use it. The plastic ones from camping supply are light and easy to carry, so is a CD; mine lives in the map pocket, but inside the space blanket would be good. It should have a hole in the middle; if not then drill an 8mm hole. To use it, hold the mirror against your eye with the reflective side away, peeping through the hole at the aircraft. Reach out with the other hand as far as you can, holding a finger tip in line with the target, and adjusting the angle of the mirror to shine the reflection onto the finger tip. Practice it with a friend at your airfield and you'll see how brilliant and distinctive the flash is, even at a great distance. ELT Well of course every aircraft should carry an Emergency Locator Transmitter. The little pocket ones are excellent, and affordable — no logical reason not to carry one these days. They're really effective, as I've proven a couple of times — both times I could have been rescued really quickly if the emergency was real. Those false alarms were just embarrassing, but it's very consoling to know that the system works so well. But the ELT must 'live' in the aircraft at all times, even for short local flights. Work out some form of mounting so that the ELT is permanently near at hand, but can be quickly removed if a speedy exit is needed. Food Food is certainly the most over-rated item in most survival manuals. All that talk of chasing around looking for little bits of 'bush tucker' and trapping animals is nonsense — far better to just lay still and conserve the reserves of energy your body already has in store. We can all go for a couple of days without any food at all, and some could even benefit from the enforced diet! Some care also needs to be taken in selecting food to carry along. For example, the often recommended 'beef jerky' would be absolutely the worst selection I could think of — not only is it a desiccated product that needs water to reconstitute, and salty that needs water to balance, but all such meat protein foods need even more water for the digestion process. It's not as if we need body-building protein in that situation — we need energy, easily digested energy. So I carry tubes of Nestle's sweetened condensed milk! Yes, it's by far the best 'survival' food that I can find. It has heaps of sugar for that instant energy, and milk for sustained energy, and the little bit of fat and protein that makes the stomach feel like it's had at least a bit of a feed. If you also have a little billycan hidden away in the aircraft, then Nestle's milk in hot water makes a very warming and sustaining drink on a cold, wet night. In a pinch you can just suck it out of the tube, along with comforting memories of childhood. So, inside my rolled up space blanket I also carry a tube of Nestle's, just in case ... I usually have several muesli bars stashed away in a pocket under the seat of my aircraft. They're for snack food and 'flying breakfasts', but would make good survival food — if enough water was at hand. Repellant Last, but not least, I reckon insect repellant is an essential to good survival. Not only do mossies drink your precious blood, but a night spent fighting them means the next day being so tired that you can't even think straight — and sufficient rest for clear thinking really is an essential for survival. Many survival crises have been made much worse by muddled thinking and panic, often brought on by exhaustion, so this is important. Just the smallest bottle available, or those individually packaged 'wipes', is all that's needed. Clothing Shouldn't even have to mention this, but a hat can make a real big difference for comfort, and even the chances of survival in either cold rain or hot sun. If you don't wear a hat regularly, then at least include one in the survival kit. My insulated flying jacket comes with me in the aircraft all the time, winter and summer. My ski pants are stashed out the way in the wing all the time. With the jacket and ski pants and the space blanket, and a good fire, I can be pretty comfortable on even a very cold night. So the minimum 'survival kit' that I reckon should be in any aircraft, all the time, (space blanket, lighters, mirror, repellant, ELT ) weighs less than a kilo, plus two kilos of water. So that's 3 kg for enough gear to survive for a day and a night without too much distress – sure sounds a lot better to me than being out there with nothing! STRICT COPYRIGHT JOHN BRANDON AND RECREATIONAL FLYING (.com)

-

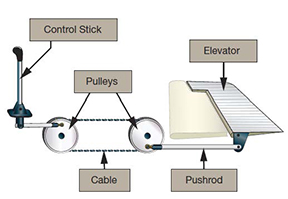

One of my early instructors was a highly pessimistic individual, always muttering about 'What if this bit fell off, how would you cope with it?" and other such comments full of joy. Over the years however, I have come across a number of incidents where things have fallen off, with widely differing results. A few years ago a gliding friend suffered a failure of an aileron quick-release control rod which caused the free aileron to flutter. An uncomfortable but still somewhat controllable situation. Unfortunately when she tried to turn the glider the loose end of the rod jammed in the structure and resulted in a high speed fatal descent. Another friend found himself at the top of a glider winch launch with no elevator control and escaped by parachute from only 600 feet. A third gliding friend flying a Nimbus 3 (an 87 feet span monster with several flap/aileron sections) aero tow-launched after a servicing during which the controls 'adjusted'. The test flight revealed the glider would only circle to the left despite full right aileron and rudder. After an interesting launch, where the tug pilot managed to turn and climb at the best rate for the glider, he was dropped off tow high enough to bale out. By experimenting with various speeds, flap and airbrake settings he managed to control it just enough to return to the airfield. By having a sound knowledge of the aircraft and approaching the problem in a calm efficient manner this pilot recovered a situation which might have ended very differently. The aim of this article is to encourage pilots to think about how they might cope with a control problem, and what aspects of the aircraft behaviour might be of assistance. While most control failure problems can be avoided by suitable maintenance there is always the possibility that one day you may find yourself with such a challenge. The key to surviving such an experience is a thorough knowledge of the handling characteristics of the aircraft, particularly the secondary effects of controls. Control failure modes Control failures, be they caused by mechanical failure, collision or structural failure will probably result in one or more of the following: restricted or no movement of the control surface surface floating free and probably fluttering to some extent surface missing completely, or connected by control cables and probably flailing around behind the aircraft major application of one or more controls to remain in a desired attitude/heading. Pitch control Perhaps the most critical control and also the one with most options, as most aircraft can be controlled in pitch in a number of ways. Adjusting the power setting will usually result in a trim change. Coarse or gentle applications of power may have different effects on attitude, descent rate and the all-important airspeed. Varying the power will also adjust torque and slipstream effect, thus assisting, to a small degree, with roll control. Aerodynamic trim tabs (those that sit on the trailing edge of the elevator) may be of some use. If the surface is jammed the tab will work like a small, albeit not very effective, elevator, although the lever must be moved the opposite way to the control column. (Trim lever forward will raise the nose). If the elevator is floating free (and not fluttering) the trim lever may be used in the same sense as the control column. Bank angle is an effective way of controlling pitch. We all know that as we enter a turn the nose tends to drop unless we counter it. It is possible to use bank angle to lower the nose and hence control the speed. You will of course be in some sort of (probably descending) turn but the turn will be partially controlled and that is better than spinning or stalling. The steeper the bank, the more the nose pitches down. By adding pro-turn or anti-turn rudder more control is available. This method gives you a reasonable degree of control over speed, in return for some height loss and the increased risk of a cross-controlled stall. Centre of gravity. If your aircraft has more than one tank and you can transfer fuel you may be able to adjust the attitude by moving fuel. Even leaning forward or back will have some effect. It's not much but it's better than nothing. A Miles Messenger escaping to England during WW2 lost its entire engine after one propeller blade was shot away while crossing the Channel. The family aboard all piled into the front seats and the aircraft glided just above the stall to shore and a successful landing! Several aircraft have approach control devices such as flaps or spoilers. These controls usually have some sort of trim change associated with their operation. Some higher performance gliders use flap settings even more than the elevator for controlling pitch, relegating the elevator to little more than a trimming device for much of the time. Roll control In the event of loss of the ailerons some degree of roll control is available by using the secondary effect of rudder. While not an efficient way to turn the aircraft you should have at least some directional control. Short or rapid bursts of power may increase the effectiveness of the rudder to some degree. Power, in the form of torque and slipstream effect may also be of use. Yaw control Loss of the rudder, as long as the aircraft is kept away from a stall/spin poses the fewest problems as long as the effects of power and adverse yaw are understood. Bank angle can be used to counter any yaw tendency (from torque or a damaged fin while in flight) and care must be taken to allow for adverse yaw when entering or exiting any turns. Effect of airspeed The various trim changes associated with controlling the aircraft change with the airspeed. Adverse yaw for example, decreases with an increase in airspeed. The aircraft should be flown at a speed safely above the stall but no faster, unless the increase in speed provides more control. If a control surface is floating free it will tend to flutter and the violence of the flutter will increase with speed. Other methods Some aircraft have doors or canopies fitted which if opened in flight may well provide some sort of trim change. It may or may not be of use but it is worth considering. If the aircraft is approved, the manufacturer may be able to supply information on what happens when a door is opened in flight. Unless the door is approved for opening in flight it should not be practised, but in an emergency ... Control on the ground If possible try to find somewhere to land which is large, long and flat, and as into wind as possible. On the ground the ailerons (or more accurately, adverse yaw) can be used to aid in directional control. (Use left aileron to turn right). Those with differential brakes can make use of them for some directional control. As many of us fly taildraggers with single brake controls, use brakes only gently and while travelling straight. Heavy braking when the aircraft is starting to swing will accelerate the impending ground loop. Considerations When faced with some control problem you should endeavour to place the aircraft in a reasonable attitude with sufficient speed for normal flight or as near as possible to it. Assess the failure as to what type (whether the failure is a structural or mechanical one and whether the surface is still there, fluttering etc.), which control(s) are affected and the various secondary effects that can be used to help. In the event of a structural failure or collision the airframe integrity will already have been compromised and so the aircraft should be landed as soon as possible, once some manner of control has been established. Extending flaps or spoilers, or opening doors on a damaged airframe may compromise the structure further so, unless control is inadequate, leave flaps where they are. If the control surface or the structure is fluttering, once again, land as soon as control is established. Flutter can be very violent and destructive, and will increase dramatically with airspeed, so aim to fly at the minimum speed where you still retain sufficient control. If the control failure is a restriction or loss of movement and you have the aircraft under sufficient control, it may be flown to a more suitable area for landing. However, continue to monitor the problem and be prepared to land immediately if there is any sign of the problem compounding. All of the above methods of alternative control, even those that only provide a small measure of assistance, may well add up to the difference between surviving a control problem or not. Even if you never have a control failure, considering the above methods will hopefully make you more aware of the aircraft's habits and so improve your flying skills. Many of these methods may be practised safely at a suitable height. For example, trim the aircraft to fly "hands off' and try a number of climbing and descending turns, rolling out onto specific headings, using rudder and effects of power. With an aircraft as responsive to secondary effects as a Drifter it is possible to fly entire circuits without touching the stick, but it is best to practise this with an instructor. Hopefully none of us will ever have to cope with a control failure but it would be nice to know how the aircraft (and the pilot) might react to one. After all none of us want to have an engine failure but we all practise in case we get one (don't we ... ?). Read the article 'Rooted' in the May – June 2004 issue of CASA's Flight Safety Australia magazine.

-